-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kimberly F Ingersoll, Yue Zhao, Grant P Harrison, Yang Li, Lian-He Yang, Endi Wang, Limited Tissue Biopsies and Hematolymphoid Neoplasms: Success Stories and Cautionary Tales, American Journal of Clinical Pathology, Volume 152, Issue 6, December 2019, Pages 782–798, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqz107

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Use of fine-needle aspiration/needle core biopsy (FNA/CNB) in evaluating hematolymphoid processes has been debated. We investigate its applicability in various clinicopathologic settings.

We retrospectively analyzed 152 cases of FNA/CNB.

Of 152 FNA/CNBs, 124 (81.6%) resulted in diagnoses without excisional biopsies, while 28 required subsequent excisional biopsies. Of these, 43 FNA/CNBs performed for suspected lymphoma relapse demonstrated 95.4% diagnostic rate (41/43), which was significantly better than those without history of lymphoma (77/109, 71%; odds ratio [OR], 8.5; confidence interval, 1.9-37.4). Patients with immunodeficiency also showed a high rate of diagnosis by FNA/CNB (100%). When stratified by types of disease, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma/high-grade B-cell lymphoma demonstrated a higher success rate (92.7%) than small B-cell lymphoma (79.2%), though the difference was not statistically significant (OR, 3.3; P value = .07). A subsequent excisional biopsy was required in 28 cases, 23 of which resulted in diagnoses concordant with the FNA/CNB. Five cases showed diagnostic discordance, reflecting pitfalls of FNA/CNB in unusual cases with complex pathology.

FNA/CNB is practical in evaluating most hematolymphoid lesions, with high efficacy in recurrent disease and some primary neoplasms with homogeneous/ aggressive histology, or characteristic immunophenotype.

Limited tissue biopsy, including both fine-needle aspiration biopsy and core needle biopsy (FNA/CNB), is a minimally invasive procedure that may be used as a primary diagnostic tool for a multitude of disease processes.1 There are limited adverse effects associated with performing an FNA/CNB due to the small-caliber needle used as compared to the instruments used to perform an incisional biopsy or excisional biopsy, which may require anesthetic sedation in an operating room.1-4 Additionally, FNA/CNB may allow for a more rapid pathologic evaluation compared to conventional histologic evaluation.5 Therefore, FNA/CNB is the initial tool used for many disease processes when tissue procurement is required for diagnosis and treatment.1,5 However, hematolymphoid neoplasms present a unique challenge to diagnosis by FNA/CNB as a number of ancillary studies, including flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, florescence in situ hybridization, and molecular testing, are often required to render an accurate diagnosis and classification of these lesions. FNA/CNB may not provide sufficient tissue to perform all these tests.2,6-19 Additionally, diagnoses of hematolymphoid neoplasms often hinge on architectural alterations, which may not be well represented in an FNA/CNB as compared to an incisional or excisional biopsy.13

Prior studies have demonstrated that FNA is effective in the assessment of approximately 70% to 90% of hematolymphoid neoplasms.1,5,12,18,20-22 It has been reported that FNA demonstrates a lower yield in certain types of hematolymphoid neoplasms, including cases of mature T-cell lymphoma, T-cell–rich large B-cell lymphoma, and lymphomas that have sclerotic changes, such as mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL).12,23-25 These cases often pose a diagnostic challenge on the evaluation of smears or touch preparation slides; nonetheless, the addition of a cell block or core biopsy with immunohistochemical evaluation may enhance the diagnostic accuracy.12,22,24 Thus, in the correct clinicopathologic context and with adequate sampling, FNA/CNB has been shown to be a useful tool in the evaluation of patients with lesions suspicious for hematolymphoid processes.4,12,14,20,21,26 However, false-negative and false-positive cases have been noted in previous studies.6,20,27 This leaves a cohort of patients with suspected hematolymphoid neoplasms who may be misdiagnosed and mistreated based on FNA/CNB analysis if a subsequent excisional biopsy is not performed. Therefore, for both pathologists and clinicians, it is imperative to understand the limitations of FNA/CNB in the evaluation of hematolymphoid neoplasms, and it is important to understand in which clinical scenarios FNA/CNB can provide a reliable diagnosis, and in which clinical situations and pathologic contexts an excisional biopsy is more appropriate.12,14,20,26,27

The purpose of this study is to expand upon prior studies that have identified situations in which FNA/CNB is unsuccessful in evaluating patients with suspected hematolymphoid neoplasms. This study aims to further stratify which patients may benefit from an FNA/CNB as the primary procedure in the diagnosis of a hematolymphoid neoplasm, and which cases carry potential pitfalls and may benefit from excisional biopsy for definitive diagnosis and precise classification.

Materials and Methods

Case Selection

Following approval of this study by the institutional review board of Duke University Medical Center, we retrieved 152 hematolymphoid FNA/CNB cases from our pathology database from January 2017 to August 2018. Clinical histories and laboratory data, including flow cytometric analyses, cytogenetic studies, and molecular diagnostic tests, were collected and retrospectively reviewed and analyzed. All of the cases were evaluated by hematopathologists (K.F.I., Y.Z., and E.W.) at Duke University Hospital, and the diagnosis of each individual case was confirmed according to the World Health Organization classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues.28

Fine-Needle Aspiration and Core Needle Biopsy

All percutaneous FNAs were performed using a 0.6-mm needle according to the standard procedure. The lesion was approached by palpation, if it was superficial. Deep lesions were localized using ultrasound or computed tomography scan. Immediate evaluation was performed on each aspirate smear and/or touch imprint to assess for specimen adequacy.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22 (www.ibm.com). X2 testing was used to assess the statistical significance of differences between groups or between categories.

Results

Rates of FNA/CNB Diagnosis and Clinical Parameters

Of the total 152 patients, 80 (52.6%) were male and 72 (47.4%) were female. The patient’s age ranged from 11 to 85 years, with a median age of 63 years. Of the 152 cases, 61 cases (40.1%) were biopsies of an enlarged superficial lymph node, 56 cases (36.8%) were biopsies of a deep lymph node, and 35 cases (23.0%) targeted lesions in an internal organ or in the deep soft tissue. The clinical indication for the biopsy included a possible relapse of lymphoma in 43 cases (28.3%), a risk of immunodeficiency-related (such as organ transplant or human immune deficiency-associated) lymphoma in five cases (3.3%), and other indications in 104 cases (68.4%). The majority of the cases were evaluated by a cytopathologist initially and were subsequently referred to a hematopathologist for evaluation. Of the 152 total cases, 124 cases (81.6%) had sufficient tissue to allow for a reliable diagnosis to be rendered on FNA/CNB and did not require a subsequent excisional biopsy. However, 28 cases (18.4%) required a subsequent excisional biopsy for additional evaluation or classification of the lesion.

In the 43 patients with a previous history of lymphoma, 41 cases (95.4%) resulted in a definitive diagnosis on FNA/CNB without the need to perform an excisional biopsy. In contrast, of the 109 patients who had no prior history of lymphoma, 77 cases (71%) resulted in diagnosis by FNA/CNB alone. The rate of diagnosis on FNA/CNB without requiring a subsequent excisional biopsy was significantly higher in patients with a history of lymphoma than in those without (odds ratio [OR], 8.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.94-37.35; P value = .001). Five patients had history of immunodeficiency secondary to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (one patient) or solid organ transplantation (four patients). None of these patients required a subsequent excisional biopsy for further evaluation (100%). Of these five patients, four were diagnosed as posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD), including monomorphic type in two patients and polymorphic type in the other two. The remaining patient was diagnosed as HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Epstein-Barr virus was positive in three cases of PTLD.

The patient’s age or gender, the presenting symptoms, the site of biopsy, the imaging findings, or the type of biopsy (palpation guided, ultrasound guided, computed tomography-guided, endoscopic, etc) did not have an impact on whether or not the patient required a subsequent excisional biopsy.

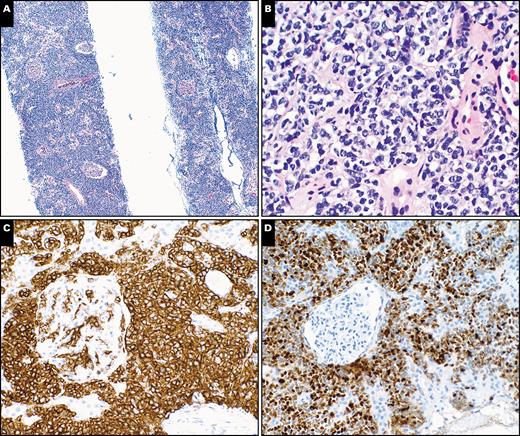

An example in which the patient’s history of lymphoma aided in the diagnosis rendered on FNA/CNB is illustrated by the case described in Image 1. In this example, a 61-year-old man had a history of HIV infection and a previous diagnosis of cHL. He presented with abdominal lymphadenopathy, suspicious for lymphomatous relapse. FNA demonstrated features suggestive of cHL (Image 1); however, the findings were insufficient to render a definitive diagnosis based on this FNA and cell block in isolation. Nevertheless, the morphologic findings in context of the patient’s history of cHL allowed for a diagnosis of recurrent cHL to be made. In this case, the diagnosis was correlated with the clinical findings, and the patient was treated appropriately. Similarly, it would be difficult to reach a definitive diagnosis for the two cases of polymorphic variant of PTLD without history of organ transplantation.

Cytopathologic evaluation of a fine-needle aspiration biopsy of a celiac lymph node demonstrating classic Hodgkin lymphoma in a 61-year-old male patient with HIV infection and a history of classic Hodgkin lymphoma. A, Papanicolaou stain of fine-needle aspirate smear shows a few large abnormal lymphoid cells in a background of many small lymphocytes. Note large multinucleated cells with prominent nucleoli in each nuclear lobe (×400). B, H&E-stained cell block section shows small fragments of lymphoid tissue with heterogeneous cell populations. Note the ample amount of eosinophilic staining suggestive of a possible histiocytic infiltrate (×200). C, Stain for CD30 highlights a few scattered large cells (×400). D, CD15 stain shows positivity in a few large cells (×400). E, The large cells are positive for PAX5. Note the positive large cells are present in B-cell–spared microenvironment (×200). F, Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNAs in situ hybridization demonstrates scattered positive cells that are large in size and correlate with CD30, CD15, and PAX5 positive cells (×200).

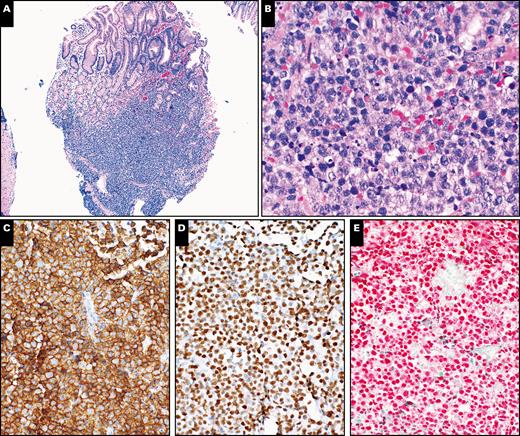

The adequacy of the FNA/CNB in performing ancillary testing was also analyzed. Of the 152 total cases, 116 cases (76.3%) collected adequate diagnostic material for both flow cytometric analysis and cell block/core biopsy preparation. Twenty-nine cases (19.1%) collected material for a cell block/core biopsy only and flow cytometric analysis was not performed. There were seven cases (4.6%) in which a sample was submitted for flow cytometric analysis; however, a core biopsy/cell block was not available for evaluation. No cases were identified in which neither flow cytometric analysis nor a cell block/core biopsy was present for evaluation. There was no statistically significant difference in the diagnostic accuracy of FNA/CNB depending on the availability of cell block/core biopsy with or without flow cytometric analysis. However, an adequate cell block/core biopsy with immunohistochemical analysis anecdotally allows for further classifications of certain lesions, such as in the grading of follicular lymphoma. As an example, Image 2 demonstrates a CNB of a 68-year-old woman with right axillary lymphadenopathy suspicious for metastatic carcinoma. CNB with immunohistochemistry demonstrated features consistent with follicular lymphoma. The cores contained a proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid follicles comprised of a homogenous population of centrocytes without an increase in mitotic figures. Tingible body macrophages were absent, and the proliferation index was low, as demonstrated by a Ki-67 immunohistochemical stain. Therefore, a diagnosis of low-grade follicular lymphoma was rendered due to the excellent CNB available for immunohistochemical evaluation.

Histopathologic evaluation of a core needle biopsy of the right axillary lymph node showing low-grade follicular lymphoma in a 68-year-old woman. A, H&E-stained section shows needle core of lymphoid tissue with a nodular growth pattern. Note the absence of cellular polarity and tingible body macrophages in the follicle center-like nodules, and the attenuated mantle zones and interfollicular areas (×40). Inset shows a high magnification of atypical lymphocytes that are small in size (H&E stain, ×400). B, CD20 (red) and CD3 (brown) dual stains highlight B cells in the follicle centers and T cells in interfollicular areas (×100). C, Stain for CD10 highlights the follicle centers (×100). D, BCL2 stain shows enhanced expression of the protein within follicle centers, in contrast to the staining in interfollicular T cells (×100).

Association of Certain Diagnoses With the Accuracy of FNA/CNB

In our cohort, the diagnoses rendered on FNA/CNB included follicular lymphoma in 27 cases (17.8%), chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) in six cases (4.0%), DLBCL in 36 cases (23.7%), high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL) in five cases (3.3%), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) or lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) in 13 cases (8.6%), cHL in eight cases (5.3%), nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) in two cases (1.3%), PTLD/other Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated B-cell lymphoma in six cases (4.0%), mature T-cell lymphoma in two cases (1.3%), plasma cell neoplasm in three cases (2.0%), precursor hematolymphoid neoplasm in three cases (2.0%), nonhematolymphoid neoplasms in five cases (3.3%), and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia in 34 cases (22.4%) Table 1. When stratified by diagnosis, some entities demonstrated a higher diagnostic rate on FNA/CNB compared to the general rate of diagnosis. These entities include DLBCL Image 3 (91.7%), HGBCL (100%), plasma cell or plasmablastic neoplasm Image 4 (100%), and precursor hematolymphoid neoplasm (100%). In contrast, the diagnostic rate on FNA/CNB for follicular lymphoma (77.8%), mantle cell lymphoma (50.0%), peripheral T-cell lymphoma (50.0%), and Hodgkin lymphoma (75%) were lower than the pooled average of 81.6% (Table 1). When the cases of DLBCL were combined with the cases of HGBCL (41 cases in total), the rate of diagnosis by FNA/CNB was 92.3% (38 of 41 cases). The diagnostic rate of FNA/CNB in small B-cell lymphomas (including follicular lymphoma, CLL/SLL, mantle cell lymphoma [MCL], and MZL/LPL) was 79.2%. Therefore, FNA/CNB is more likely to render a diagnosis in cases of DLBCL/HGBCL as compared to cases of small B-cell lymphoma (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 0.9-13.1); however, this difference is not statistically significant (P value = .07), likely due to the small sample size.

| Disease . | Diagnosis by FNA/CNB . | Total No. of Cases . | Percentage Diagnosed by FNA/CNB . |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 21 | 27 | 77.8 |

| CLL/SLL | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| MCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| MZL/LPL | 11 | 13 | 84.6 |

| PCN | 3 | 3 | 100.0 |

| DLBCL | 33 | 36 | 91.7 |

| HGBCL | 5 | 5 | 100.0 |

| PTLD/EBV+LPD | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| PTCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| NLPHL | 0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| CHL | 6 | 8 | 75.0 |

| T-ALL | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| AML/MS | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| BHD | 26 | 34 | 76.5 |

| NHN | 4 | 5 | 80.0 |

| Total | 124 | 152 | 81.6 |

| Disease . | Diagnosis by FNA/CNB . | Total No. of Cases . | Percentage Diagnosed by FNA/CNB . |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 21 | 27 | 77.8 |

| CLL/SLL | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| MCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| MZL/LPL | 11 | 13 | 84.6 |

| PCN | 3 | 3 | 100.0 |

| DLBCL | 33 | 36 | 91.7 |

| HGBCL | 5 | 5 | 100.0 |

| PTLD/EBV+LPD | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| PTCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| NLPHL | 0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| CHL | 6 | 8 | 75.0 |

| T-ALL | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| AML/MS | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| BHD | 26 | 34 | 76.5 |

| NHN | 4 | 5 | 80.0 |

| Total | 124 | 152 | 81.6 |

AML/MS, acute myeloid leukemia/myeloid sarcoma; CHL, classic Hodgkin lymphoma; BHD, benign hematologic disorder; CLL/SLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; FNA/CNB, fine-needle aspiration/core needle biopsy; HGBCL, high-grade B-cell lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL/LPL, marginal zone lymphoma/lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; NHN, nonhematologic neoplasm; NLPHL, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; PCN, plasma cell neoplasm; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; PTLD/EBV+ LPD, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder/ Epstein-Barr virus-positive lymphoproliferative disorder; T-ALL, T-lymphoblastic lymphoma;

| Disease . | Diagnosis by FNA/CNB . | Total No. of Cases . | Percentage Diagnosed by FNA/CNB . |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 21 | 27 | 77.8 |

| CLL/SLL | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| MCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| MZL/LPL | 11 | 13 | 84.6 |

| PCN | 3 | 3 | 100.0 |

| DLBCL | 33 | 36 | 91.7 |

| HGBCL | 5 | 5 | 100.0 |

| PTLD/EBV+LPD | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| PTCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| NLPHL | 0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| CHL | 6 | 8 | 75.0 |

| T-ALL | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| AML/MS | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| BHD | 26 | 34 | 76.5 |

| NHN | 4 | 5 | 80.0 |

| Total | 124 | 152 | 81.6 |

| Disease . | Diagnosis by FNA/CNB . | Total No. of Cases . | Percentage Diagnosed by FNA/CNB . |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 21 | 27 | 77.8 |

| CLL/SLL | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| MCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| MZL/LPL | 11 | 13 | 84.6 |

| PCN | 3 | 3 | 100.0 |

| DLBCL | 33 | 36 | 91.7 |

| HGBCL | 5 | 5 | 100.0 |

| PTLD/EBV+LPD | 5 | 6 | 83.3 |

| PTCL | 1 | 2 | 50.0 |

| NLPHL | 0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| CHL | 6 | 8 | 75.0 |

| T-ALL | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| AML/MS | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| BHD | 26 | 34 | 76.5 |

| NHN | 4 | 5 | 80.0 |

| Total | 124 | 152 | 81.6 |

AML/MS, acute myeloid leukemia/myeloid sarcoma; CHL, classic Hodgkin lymphoma; BHD, benign hematologic disorder; CLL/SLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; FNA/CNB, fine-needle aspiration/core needle biopsy; HGBCL, high-grade B-cell lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL/LPL, marginal zone lymphoma/lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; NHN, nonhematologic neoplasm; NLPHL, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; PCN, plasma cell neoplasm; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; PTLD/EBV+ LPD, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder/ Epstein-Barr virus-positive lymphoproliferative disorder; T-ALL, T-lymphoblastic lymphoma;

Histopathologic evaluation of a core needle biopsy of kidney with a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, germinal center phenotype, in a 68-year-old female patient with a remote history of large B-cell lymphoma. A, H&E-stained needle core section shows renal tissue with an interstitial infiltrate of lymphoid cells. Note the relatively intact glomeruli (×40). B, High magnification shows medium-sized to large lymphoid cells with irregular nuclear contours, vesicular chromatin, and moderate amount of clear cytoplasm in renal interstitial space (H&E, ×400). C, Stain for CD20 highlights interstitial infiltrate of the medium-sized to large lymphoid cells (×200). D, Ki-67 stain shows an increased proliferative index of the interstitial lymphoid cells (×200).

Histopathologic evaluation of upper gastrointestinal endoscopic biopsy of stomach lesion with plasmablastic lymphoma in a 58-year-old male patient. A, H&E-stained section shows gastric mucosa with submucosal infiltrate of lymphoid cells (×40). B, A high magnification shows morphologic features of large lymphoid cells. Note the relatively abundant cytoplasm in abnormal large cells and increased apoptotic bodies (H&E, ×400). C, The large cells are positive for CD138 (×200). D, Stain for OCT2 highlights the large lymphoid cells (×200). E, Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNAs in situ hybridization shows positive staining in the large lymphoid cells (×200).

Diagnostic Concordance Between FNA/CNB and Subsequent Excisional Biopsy

Of the 28 cases requiring subsequent excisional biopsy, 14 cases (50.0%) underwent an excisional biopsy to confirm the diagnosis or for additional classification of the lesion. Five cases (17.9%) underwent a subsequent excisional biopsy to obtain a histologic grade for cases of follicular lymphoma. The remaining nine cases (32.1%) underwent an excisional biopsy due to diagnostic uncertainty. The subsequent excisional biopsies resulted in a concordant diagnosis with the FNA/CNB evaluation in 23 cases (82.1%). However, five cases (17.9%) yielded a discordant diagnosis between FNA/CNB and the subsequent excisional biopsy. These five cases with diagnostic discordance were due to inaccurate histologic grading of follicular lymphoma, incorrect categorization of cHL as a T-cell lymphoma, incorrect categorization of EBV-positive DLBCL as possible reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, missing neoplastic T-cell component of a composite T-cell and B-cell lymphoma, and incorrect categorization of a small B-cell lymphoma with intense reactive T-cell infiltrate as a T-cell lymphoma Table 2. Each case with discordant findings between the FNA/CNB and the subsequent excision is discussed in detail below.

Clinicopathologic Information in 28 Cases of FNA/CNB and Subsequent Excisional Biopsy

| Case . | Age, y . | Sex . | Presentation . | Radiology . | Biopsy Site . | FNA Smear . | CB/CNB . | IHC . | FC . | FNA/CNB Diagnosis . | Excisional Biopsy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | F | Left neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, rare large | Miniscule tissue | NP | Neg | Suggestive of reactive hyperplasia | EBV+LBCL |

| 2 | 51 | M | Leukocytosis adenopathy | Generalized adenopathy (CT) | Groin LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | T cells | Pos | Suggestive of T-cell lymphoma | SLL/CLL |

| 3 | 49 | M | Diffuse adenopathy | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, plasma cells | Interfollicular lymphoplasmacytes | B cells | B cells | Suggestive of MZL/LPL | Composite B-/T-cell lymphoma |

| 4 | 47 | M | H/O CHL | PET, mesenteric adenopathy | Mesenteric mass | Mixed small-large cells | Follicular growth | CD10+ B cells | NP | Low-grade FL | DLBCL, FL G3 |

| 5 | 70 | M | Back pain | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | Lymphocytes | Tiny CB | NP | T cells | Atypical T cells | CHL |

| 6 | 43 | M | Neck mass | PET Paratracheal mass | Neck mass | Rare cells | Malignant spindle cells | Dendritic cells | Neg | Malignant neoplasm | FDCS |

| 7 | 73 | F | H/O breast cancer | PET cervical adenopathy | Neck LN | Small cells | CD10+ B cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of low-grade FL | FL G1-2 |

| 8 | 30 | M | Incidental finding | Mediastinal adenopathy | Level 4R LN | Granulomas | Granulomas | NP | Neg | Suggestive of sarcoidosis | Sarcoidosis (lung wedge) |

| 9 | 67 | M | Back pain | PET diffuse adenopathy | Inguinal LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | MCL, blastoid variant |

| 10 | 69 | M | Parotid mass | PET parotid, lung lesions | Parotid mass | Atypical cells | Atypical cells | NP | Neg | Suggestive of lymphoma | PTCL NOS |

| 11 | 62 | M | Neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Polymorphous cells | Indeterminant | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | RFH |

| 12 | 65 | M | Lung mass | Lung mass, hilar adenopathy | Station 11R LN | Lymphocytes | Scant lymphoid tissue | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | Small cell carcinoma |

| 13 | 28 | F | Respiratory symptoms | Calcified hilar adenopathy | Station 11L LN | Bronchial epithelium | LN with granulomas | NP | Neg | Noncaseating granulomas | Noncaseating granulomas |

| 14 | 81 | F | Pelvic mass | PET diffuse adenopathy | Pelvic mass | Large cells | Large cells | Lymphoid | Neg | Lymphoma, B-cell type | DLBCL |

| 15 | 73 | M | Incidental finding | PET mediastinal mass, hilar LN | Hilar LNs | Polymorphous cells | Lymphoid tissue | NP | Pos | B-cell lymphoma | FL G1-2 |

| 16 | 76 | F | Incidental finding | Mesenteric mass | Mesenteric mass | Small cells, rare large | Small cells, rare large cells | NP | Pos | Small B-cell lymphoma | Small mature B-cell lymphoma |

| 17 | 57 | M | Incidental finding | PET + diffuse adenopathy | Retroperitoneal LN | Mixed small-large cells | Mixed small-large cells | Pos | Neg | Suspicious for NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 18 | 61 | F | Erythroderma axillary LN | NP | Axillary LN | Small cells | NP | NP | Neg | Predominant T cells | Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy |

| 19 | 45 | M | Pancytopenia | Pelvic and inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | Small cell | Tiny fragments of lymphoid tissue | Neg | Neg | RFH | RFH |

| 20 | 77 | M | Conjunctival lesion | NP | Conjunctival lesion | NA | Small mature lymphocytes | B cells | NP | MALT lymphoma | MALT lymphoma |

| 21 | 71 | F | Adenopathy | Diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Scattered large cells | Pos | NP | CHL | CHL |

| 22 | 63 | M | Left groin swelling | Inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Small cells | Neg | Neg | Suggestive of reactive | RFH |

| 23 | 36 | M | Neck mass | Submandibular gland mass (US) | Submandibular mass | Small cells | Scant tissue | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma |

| 24 | 48 | F | Incidental finding | Abdominal and axillary LN | Axillary LN | NA | Effaced nodal architecture | Pos | NP | Suggestive of NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 25 | 66 | F | Routine mammogram | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Small cells | Pos | Pos | FL G1 | FL G1 |

| 26 | 32 | F | Fatigue, WL, and anemia | PET, cervical, mediastinal LN | Supraclavicular LN | Scattered large cells | RS cells or variants | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of CHL | CHL |

| 27 | 46 | F | Cervical adenopathy | Neck, thoracic LN | Cervical LN | NA | Monomorphic small cells | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of FL | FL G2 |

| 28 | 76 | M | B symptoms, hypercalcemia | Retroperitoneal large mass (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Large cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of large B-cell lymphoma | DLBCL |

| Case . | Age, y . | Sex . | Presentation . | Radiology . | Biopsy Site . | FNA Smear . | CB/CNB . | IHC . | FC . | FNA/CNB Diagnosis . | Excisional Biopsy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | F | Left neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, rare large | Miniscule tissue | NP | Neg | Suggestive of reactive hyperplasia | EBV+LBCL |

| 2 | 51 | M | Leukocytosis adenopathy | Generalized adenopathy (CT) | Groin LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | T cells | Pos | Suggestive of T-cell lymphoma | SLL/CLL |

| 3 | 49 | M | Diffuse adenopathy | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, plasma cells | Interfollicular lymphoplasmacytes | B cells | B cells | Suggestive of MZL/LPL | Composite B-/T-cell lymphoma |

| 4 | 47 | M | H/O CHL | PET, mesenteric adenopathy | Mesenteric mass | Mixed small-large cells | Follicular growth | CD10+ B cells | NP | Low-grade FL | DLBCL, FL G3 |

| 5 | 70 | M | Back pain | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | Lymphocytes | Tiny CB | NP | T cells | Atypical T cells | CHL |

| 6 | 43 | M | Neck mass | PET Paratracheal mass | Neck mass | Rare cells | Malignant spindle cells | Dendritic cells | Neg | Malignant neoplasm | FDCS |

| 7 | 73 | F | H/O breast cancer | PET cervical adenopathy | Neck LN | Small cells | CD10+ B cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of low-grade FL | FL G1-2 |

| 8 | 30 | M | Incidental finding | Mediastinal adenopathy | Level 4R LN | Granulomas | Granulomas | NP | Neg | Suggestive of sarcoidosis | Sarcoidosis (lung wedge) |

| 9 | 67 | M | Back pain | PET diffuse adenopathy | Inguinal LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | MCL, blastoid variant |

| 10 | 69 | M | Parotid mass | PET parotid, lung lesions | Parotid mass | Atypical cells | Atypical cells | NP | Neg | Suggestive of lymphoma | PTCL NOS |

| 11 | 62 | M | Neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Polymorphous cells | Indeterminant | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | RFH |

| 12 | 65 | M | Lung mass | Lung mass, hilar adenopathy | Station 11R LN | Lymphocytes | Scant lymphoid tissue | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | Small cell carcinoma |

| 13 | 28 | F | Respiratory symptoms | Calcified hilar adenopathy | Station 11L LN | Bronchial epithelium | LN with granulomas | NP | Neg | Noncaseating granulomas | Noncaseating granulomas |

| 14 | 81 | F | Pelvic mass | PET diffuse adenopathy | Pelvic mass | Large cells | Large cells | Lymphoid | Neg | Lymphoma, B-cell type | DLBCL |

| 15 | 73 | M | Incidental finding | PET mediastinal mass, hilar LN | Hilar LNs | Polymorphous cells | Lymphoid tissue | NP | Pos | B-cell lymphoma | FL G1-2 |

| 16 | 76 | F | Incidental finding | Mesenteric mass | Mesenteric mass | Small cells, rare large | Small cells, rare large cells | NP | Pos | Small B-cell lymphoma | Small mature B-cell lymphoma |

| 17 | 57 | M | Incidental finding | PET + diffuse adenopathy | Retroperitoneal LN | Mixed small-large cells | Mixed small-large cells | Pos | Neg | Suspicious for NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 18 | 61 | F | Erythroderma axillary LN | NP | Axillary LN | Small cells | NP | NP | Neg | Predominant T cells | Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy |

| 19 | 45 | M | Pancytopenia | Pelvic and inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | Small cell | Tiny fragments of lymphoid tissue | Neg | Neg | RFH | RFH |

| 20 | 77 | M | Conjunctival lesion | NP | Conjunctival lesion | NA | Small mature lymphocytes | B cells | NP | MALT lymphoma | MALT lymphoma |

| 21 | 71 | F | Adenopathy | Diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Scattered large cells | Pos | NP | CHL | CHL |

| 22 | 63 | M | Left groin swelling | Inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Small cells | Neg | Neg | Suggestive of reactive | RFH |

| 23 | 36 | M | Neck mass | Submandibular gland mass (US) | Submandibular mass | Small cells | Scant tissue | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma |

| 24 | 48 | F | Incidental finding | Abdominal and axillary LN | Axillary LN | NA | Effaced nodal architecture | Pos | NP | Suggestive of NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 25 | 66 | F | Routine mammogram | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Small cells | Pos | Pos | FL G1 | FL G1 |

| 26 | 32 | F | Fatigue, WL, and anemia | PET, cervical, mediastinal LN | Supraclavicular LN | Scattered large cells | RS cells or variants | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of CHL | CHL |

| 27 | 46 | F | Cervical adenopathy | Neck, thoracic LN | Cervical LN | NA | Monomorphic small cells | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of FL | FL G2 |

| 28 | 76 | M | B symptoms, hypercalcemia | Retroperitoneal large mass (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Large cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of large B-cell lymphoma | DLBCL |

CB, cell block; CHL, classic Hodgkin lymphoma; CLL/SLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; CNB, core needle biopsy; CT, computed tomography; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; FC, flow cytometry; FDCS, follicular dendritic cell sarcoma; FL G1, follicular lymphoma, grade 1; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; H/O, history of; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LN, lymph node or lymphadenopathy; MALT lymphoma, extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL/LPL, marginal zone lymphoma/lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; NA, not available; Neg, negative or nondiagnostic findings; NLPHL, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; NP, not performed; PET, positron emission tomography; Pos, positive, the findings are consistent with the final diagnosis based on excisional biopsy; PTCL NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; RFH, reactive follicular hyperplasia; RS cells, Reed-Sternberg cells; US, ultrasound; WL, weight loss.

Clinicopathologic Information in 28 Cases of FNA/CNB and Subsequent Excisional Biopsy

| Case . | Age, y . | Sex . | Presentation . | Radiology . | Biopsy Site . | FNA Smear . | CB/CNB . | IHC . | FC . | FNA/CNB Diagnosis . | Excisional Biopsy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | F | Left neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, rare large | Miniscule tissue | NP | Neg | Suggestive of reactive hyperplasia | EBV+LBCL |

| 2 | 51 | M | Leukocytosis adenopathy | Generalized adenopathy (CT) | Groin LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | T cells | Pos | Suggestive of T-cell lymphoma | SLL/CLL |

| 3 | 49 | M | Diffuse adenopathy | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, plasma cells | Interfollicular lymphoplasmacytes | B cells | B cells | Suggestive of MZL/LPL | Composite B-/T-cell lymphoma |

| 4 | 47 | M | H/O CHL | PET, mesenteric adenopathy | Mesenteric mass | Mixed small-large cells | Follicular growth | CD10+ B cells | NP | Low-grade FL | DLBCL, FL G3 |

| 5 | 70 | M | Back pain | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | Lymphocytes | Tiny CB | NP | T cells | Atypical T cells | CHL |

| 6 | 43 | M | Neck mass | PET Paratracheal mass | Neck mass | Rare cells | Malignant spindle cells | Dendritic cells | Neg | Malignant neoplasm | FDCS |

| 7 | 73 | F | H/O breast cancer | PET cervical adenopathy | Neck LN | Small cells | CD10+ B cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of low-grade FL | FL G1-2 |

| 8 | 30 | M | Incidental finding | Mediastinal adenopathy | Level 4R LN | Granulomas | Granulomas | NP | Neg | Suggestive of sarcoidosis | Sarcoidosis (lung wedge) |

| 9 | 67 | M | Back pain | PET diffuse adenopathy | Inguinal LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | MCL, blastoid variant |

| 10 | 69 | M | Parotid mass | PET parotid, lung lesions | Parotid mass | Atypical cells | Atypical cells | NP | Neg | Suggestive of lymphoma | PTCL NOS |

| 11 | 62 | M | Neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Polymorphous cells | Indeterminant | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | RFH |

| 12 | 65 | M | Lung mass | Lung mass, hilar adenopathy | Station 11R LN | Lymphocytes | Scant lymphoid tissue | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | Small cell carcinoma |

| 13 | 28 | F | Respiratory symptoms | Calcified hilar adenopathy | Station 11L LN | Bronchial epithelium | LN with granulomas | NP | Neg | Noncaseating granulomas | Noncaseating granulomas |

| 14 | 81 | F | Pelvic mass | PET diffuse adenopathy | Pelvic mass | Large cells | Large cells | Lymphoid | Neg | Lymphoma, B-cell type | DLBCL |

| 15 | 73 | M | Incidental finding | PET mediastinal mass, hilar LN | Hilar LNs | Polymorphous cells | Lymphoid tissue | NP | Pos | B-cell lymphoma | FL G1-2 |

| 16 | 76 | F | Incidental finding | Mesenteric mass | Mesenteric mass | Small cells, rare large | Small cells, rare large cells | NP | Pos | Small B-cell lymphoma | Small mature B-cell lymphoma |

| 17 | 57 | M | Incidental finding | PET + diffuse adenopathy | Retroperitoneal LN | Mixed small-large cells | Mixed small-large cells | Pos | Neg | Suspicious for NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 18 | 61 | F | Erythroderma axillary LN | NP | Axillary LN | Small cells | NP | NP | Neg | Predominant T cells | Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy |

| 19 | 45 | M | Pancytopenia | Pelvic and inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | Small cell | Tiny fragments of lymphoid tissue | Neg | Neg | RFH | RFH |

| 20 | 77 | M | Conjunctival lesion | NP | Conjunctival lesion | NA | Small mature lymphocytes | B cells | NP | MALT lymphoma | MALT lymphoma |

| 21 | 71 | F | Adenopathy | Diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Scattered large cells | Pos | NP | CHL | CHL |

| 22 | 63 | M | Left groin swelling | Inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Small cells | Neg | Neg | Suggestive of reactive | RFH |

| 23 | 36 | M | Neck mass | Submandibular gland mass (US) | Submandibular mass | Small cells | Scant tissue | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma |

| 24 | 48 | F | Incidental finding | Abdominal and axillary LN | Axillary LN | NA | Effaced nodal architecture | Pos | NP | Suggestive of NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 25 | 66 | F | Routine mammogram | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Small cells | Pos | Pos | FL G1 | FL G1 |

| 26 | 32 | F | Fatigue, WL, and anemia | PET, cervical, mediastinal LN | Supraclavicular LN | Scattered large cells | RS cells or variants | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of CHL | CHL |

| 27 | 46 | F | Cervical adenopathy | Neck, thoracic LN | Cervical LN | NA | Monomorphic small cells | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of FL | FL G2 |

| 28 | 76 | M | B symptoms, hypercalcemia | Retroperitoneal large mass (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Large cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of large B-cell lymphoma | DLBCL |

| Case . | Age, y . | Sex . | Presentation . | Radiology . | Biopsy Site . | FNA Smear . | CB/CNB . | IHC . | FC . | FNA/CNB Diagnosis . | Excisional Biopsy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | F | Left neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, rare large | Miniscule tissue | NP | Neg | Suggestive of reactive hyperplasia | EBV+LBCL |

| 2 | 51 | M | Leukocytosis adenopathy | Generalized adenopathy (CT) | Groin LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | T cells | Pos | Suggestive of T-cell lymphoma | SLL/CLL |

| 3 | 49 | M | Diffuse adenopathy | NP | Neck LN | Lymphocytes, plasma cells | Interfollicular lymphoplasmacytes | B cells | B cells | Suggestive of MZL/LPL | Composite B-/T-cell lymphoma |

| 4 | 47 | M | H/O CHL | PET, mesenteric adenopathy | Mesenteric mass | Mixed small-large cells | Follicular growth | CD10+ B cells | NP | Low-grade FL | DLBCL, FL G3 |

| 5 | 70 | M | Back pain | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | Lymphocytes | Tiny CB | NP | T cells | Atypical T cells | CHL |

| 6 | 43 | M | Neck mass | PET Paratracheal mass | Neck mass | Rare cells | Malignant spindle cells | Dendritic cells | Neg | Malignant neoplasm | FDCS |

| 7 | 73 | F | H/O breast cancer | PET cervical adenopathy | Neck LN | Small cells | CD10+ B cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of low-grade FL | FL G1-2 |

| 8 | 30 | M | Incidental finding | Mediastinal adenopathy | Level 4R LN | Granulomas | Granulomas | NP | Neg | Suggestive of sarcoidosis | Sarcoidosis (lung wedge) |

| 9 | 67 | M | Back pain | PET diffuse adenopathy | Inguinal LN | Medium-large cells | Medium-large cells | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | MCL, blastoid variant |

| 10 | 69 | M | Parotid mass | PET parotid, lung lesions | Parotid mass | Atypical cells | Atypical cells | NP | Neg | Suggestive of lymphoma | PTCL NOS |

| 11 | 62 | M | Neck mass | NP | Neck LN | Polymorphous cells | Indeterminant | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | RFH |

| 12 | 65 | M | Lung mass | Lung mass, hilar adenopathy | Station 11R LN | Lymphocytes | Scant lymphoid tissue | NP | Neg | Indeterminant | Small cell carcinoma |

| 13 | 28 | F | Respiratory symptoms | Calcified hilar adenopathy | Station 11L LN | Bronchial epithelium | LN with granulomas | NP | Neg | Noncaseating granulomas | Noncaseating granulomas |

| 14 | 81 | F | Pelvic mass | PET diffuse adenopathy | Pelvic mass | Large cells | Large cells | Lymphoid | Neg | Lymphoma, B-cell type | DLBCL |

| 15 | 73 | M | Incidental finding | PET mediastinal mass, hilar LN | Hilar LNs | Polymorphous cells | Lymphoid tissue | NP | Pos | B-cell lymphoma | FL G1-2 |

| 16 | 76 | F | Incidental finding | Mesenteric mass | Mesenteric mass | Small cells, rare large | Small cells, rare large cells | NP | Pos | Small B-cell lymphoma | Small mature B-cell lymphoma |

| 17 | 57 | M | Incidental finding | PET + diffuse adenopathy | Retroperitoneal LN | Mixed small-large cells | Mixed small-large cells | Pos | Neg | Suspicious for NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 18 | 61 | F | Erythroderma axillary LN | NP | Axillary LN | Small cells | NP | NP | Neg | Predominant T cells | Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy |

| 19 | 45 | M | Pancytopenia | Pelvic and inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | Small cell | Tiny fragments of lymphoid tissue | Neg | Neg | RFH | RFH |

| 20 | 77 | M | Conjunctival lesion | NP | Conjunctival lesion | NA | Small mature lymphocytes | B cells | NP | MALT lymphoma | MALT lymphoma |

| 21 | 71 | F | Adenopathy | Diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Scattered large cells | Pos | NP | CHL | CHL |

| 22 | 63 | M | Left groin swelling | Inguinal LN (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Small cells | Neg | Neg | Suggestive of reactive | RFH |

| 23 | 36 | M | Neck mass | Submandibular gland mass (US) | Submandibular mass | Small cells | Scant tissue | NP | Pos | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma | Suggestive of B-cell lymphoma |

| 24 | 48 | F | Incidental finding | Abdominal and axillary LN | Axillary LN | NA | Effaced nodal architecture | Pos | NP | Suggestive of NLPHL | NLPHL |

| 25 | 66 | F | Routine mammogram | PET, diffuse adenopathy | Axillary LN | NA | Small cells | Pos | Pos | FL G1 | FL G1 |

| 26 | 32 | F | Fatigue, WL, and anemia | PET, cervical, mediastinal LN | Supraclavicular LN | Scattered large cells | RS cells or variants | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of CHL | CHL |

| 27 | 46 | F | Cervical adenopathy | Neck, thoracic LN | Cervical LN | NA | Monomorphic small cells | Pos | Neg | Suggestive of FL | FL G2 |

| 28 | 76 | M | B symptoms, hypercalcemia | Retroperitoneal large mass (CT) | Inguinal LN | NA | Large cells | Pos | Pos | Suggestive of large B-cell lymphoma | DLBCL |

CB, cell block; CHL, classic Hodgkin lymphoma; CLL/SLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma; CNB, core needle biopsy; CT, computed tomography; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; FC, flow cytometry; FDCS, follicular dendritic cell sarcoma; FL G1, follicular lymphoma, grade 1; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; H/O, history of; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LN, lymph node or lymphadenopathy; MALT lymphoma, extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL/LPL, marginal zone lymphoma/lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; NA, not available; Neg, negative or nondiagnostic findings; NLPHL, nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; NP, not performed; PET, positron emission tomography; Pos, positive, the findings are consistent with the final diagnosis based on excisional biopsy; PTCL NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; RFH, reactive follicular hyperplasia; RS cells, Reed-Sternberg cells; US, ultrasound; WL, weight loss.

Case 1 underwent initial FNA that showed lymphoid infiltrate with predominantly small lymphocytes Image 5A. Flow cytometry demonstrated mixed lymphoid population with predominantly T cells and polytypic B cells. Thereafter, this case was considered to represent reactive lymphadenopathy. An excisional biopsy was recommended to further confirm the diagnosis. A subsequent excisional biopsy demonstrated evidence of EBV-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder Image 5B, Image 5C, and Image 5D. While polymorphic in morphology, this case most likely represents EBV-positive DLBCL, given the focal aggregates of large cells and the clonal rearrangement of the IGH gene, detected later.

Cytologic evaluation of left submandibular lymphadenopathy and subsequent excisional biopsy of the lymph node with Epstein-Barr virus-positive lymphoproliferative disorder in a 31-year-old female patient. A, Diff-Quick-stained aspirate smear of the initial fine-needle aspiration biopsy shows a lymphoid population consisting mainly of small lymphocytes with scattered few large cells (×400). B, H&E-stained section of a subsequent excisional biopsy shows a heterogeneous population of lymphocytes with significantly increased large lymphoid cells (×400). C, Stain for CD20 highlights the large lymphoid cells that are scattered and admixed with more small B cells (×200). D, CD3 stain demonstrates fewer T cells that are small in size. Note large cells in the background appear to stain weakly for the antigen marker. Inset, Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNAs in situ hybridization shows scattered positive cells that range from small to large in size (×200).

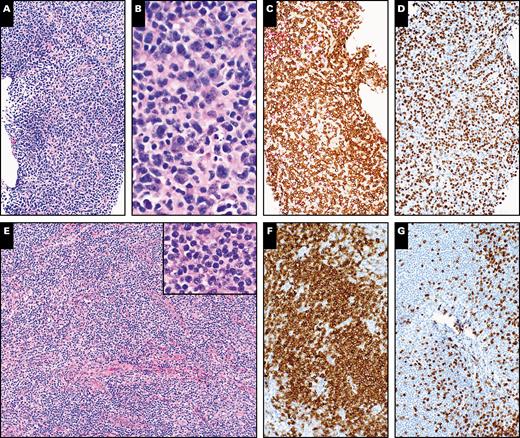

In case 2, an initial CNB yielded a small tissue core that demonstrated lymphoid tissue with predominantly small to medium-sized lymphocytes Image 6A and Image 6B. Immunohistochemical analysis showed mainly T cells with irregular nuclear contours Image 6C and rare B cells; the proliferative index was high Image 6D. Thereafter, a T-cell lymphoma was considered; however, flow cytometry demonstrated no definitively abnormal population of T cells. Instead, flow cytometry detected a small population of monoclonal B cells with aberrant CD5 and CD23. Given the discrepant results between the flow cytometric analysis and the morphologic findings, an excisional biopsy was recommended to further characterize the patient’s lymphadenopathy. On excisional biopsy, the case was diagnosed as CLL/SLL with a focally dense reactive T-cell infiltrate Image 6E, Image 6F, and Image 6G.

Histopathologic evaluation of an ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of a right groin lymph node and subsequent excisional biopsy of the same lymph node showing chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma in a 52-year-old male patient. A, H&E-stained section of the initial needle core biopsy shows lymphoid tissue without appreciable follicular architecture (×100). B, A high magnification shows small to medium-sized lymphoid cells (×400). C, CD3 stain shows many positive cells (×100). D, Increased proliferative index highlighted by Ki-67 stain (×100). E, H&E-stained section of subsequent excisional biopsy shows lymphoid tissue with nodal architecture effaced by predominantly small to medium-sized lymphoid cells (×100). Inset shows small to medium-sized lymphoid cells at high magnification (×400). F, Stain for CD20 highlights the small lymphocytes (×100). G, CD3 stain demonstrates fewer T cells that are small in size (×100).

In case 3, an CNB demonstrated an atypical lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with κ light chain restriction present in plasmacytoid cells Image 7; there was no significant atypical T-cell population on the section. The concurrent flow cytometric analysis detected a small population of monoclonal B cells. Thus, this case was initially considered to represent small mature B-cell lymphoma, and the differential included MZL or LPL due to the plasmacytoid differentiation identified. Surprisingly, a subsequent excisional biopsy showed evidence of two neoplastic components Image 8: (1) low-grade follicular lymphoma with plasmacytoid differentiation, and (2) angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, perifollicular variant. The diagnosis of two neoplastic components was supported by the flow cytometric detection of a CD10-positive monoclonal B-cell population and a CD4-positive T-cell population with CD10 and loss of surface CD3 expression. Additionally, molecular testing demonstrated both B-cell and T-cell clones present in the excisional biopsy specimen. Therefore, the final diagnosis of a composite lymphoma of T-cell and B-cell origin was rendered.

Histopathologic evaluation of a core needle biopsy of a right cervical lymph node with a composite lymphoma of B-cell and T-cell types in a 48-year-old male patient (same patient as Image 8). A, H&E-stained section shows lymphoid tissue without appreciable follicular architecture (×100). B. A high magnification shows medium-sized lymphoid cells with plasmacytoid differentiation. Note scattered eosinophils and a few apoptotic bodies (×400). C, CD20 (red) and CD3 (brown) dual stains highlight B-cell nodules and scattered T cells. Note many cells in interfollicular area are negative for both CD3 and CD20 (×100). D, CD79a stain shows positive cells that appear slightly larger than normal and are more than CD20-positive cells (×400). E and F, The plasmacytoid cells are positive for κ light chain (E) and negative for λ light chain (F) (×200).

Histopathologic evaluation of an excisional biopsy of a right groin lymph node demonstrating a composite lymphoma of B-cell and T-cell types in a 48-year-old male patient (same patient as Image 7). A, H&E-stained section shows lymph node with architectural effacement by a nodular lymphoid proliferation. Note the slightly expanded interfollicular areas with pale staining, including the halo present around the follicles (×20). B, H&E-stained section shows an individual follicle that is composed of homogeneous small lymphocytes with no cellular polarity or tangible body macrophages. Note a proliferation of high endothelial venules in the perifollicular/interfollicular area (×100). C, CD3 stain highlights perifollicular distribution of T cells (×100). D, BCL2 shows perifollicular staining consistent with perifollicular T cells, while it is negative in lymphocytes within the follicle center (×100). E, CD20 stain highlights B cells within follicle centers (×40). F, Ki-67 stain shows relatively low proliferative index within follicle centers. Note the lack of polarity and marginalized staining (×100). G, A follicle is highlighted by CD10 stain. Note a perifollicular distribution of the cells with stronger staining, presumably abnormal T cells with follicular helper phenotype (×100). H, PD1 stain shows a scattered increase in positive cells with perifollicular distribution (×100).

The CNB in case 4 demonstrated a vaguely nodular proliferation of centrocyte-like lymphoid cells that were positive for CD20, CD10, and BCL2. Thus, the case was diagnosed as low-grade follicular lymphoma. Given the small size of the biopsy, an excisional biopsy was recommended to confirm the histologic grade and growth pattern. The subsequent excisional biopsy demonstrated high-grade follicular lymphoma (grade 3A) and concurrent DLBCL of germinal center origin (data not shown).

The FNA of case 5 showed predominantly small lymphoid cells. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated a mixed lymphoid population with mainly CD4-positive T cells with a loss of CD26 expression. No monoclonal B-cell population was identified. Therefore, the case was suspected to represent a T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Due to miniscule tissue fragments present on the cell block, an excisional biopsy was suggested to further characterize the lesion. The excisional biopsy demonstrated cHL (Supplemental Image 1) (all supplemental materials can be found at American Journal of Clinical Pathology online).

In summary, the causes of incorrect diagnosis rendered on FNA/CNB in our data set may be attributed to lack of adequate tissue fragments for ancillary studies (cases 1 and 5) or due to unrepresentative CNB (sampling error or sampling bias), particularly in cases with more complex pathologic diagnoses (cases 2-4).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the applicability of FNA/CNB in the diagnosis of hematolymphoid neoplasms, as 124 of 152 cases (81.6%) were diagnosed by FNA/CNB without the need for a subsequent excisional biopsy. Similar rates of diagnostic accuracy have been reported in previous studies.1,5,12,18,20-22 The chance of a successful FNA/CNB evaluation is especially higher in a patient with a clinical history of lymphoma who has a suspected relapse or transformation, or in a patient at higher risk of developing a lymphoproliferative disorder, including patients who have undergone solid organ transplantation, or patients with HIV. The clinical approach to a patient with a suspected hematolymphoid neoplasm may be triaged based on the patient’s history so that the best diagnostic modality is utilized. Although the FNA/CNB may be limited in some cases and insufficient to render a definitive diagnosis and classification in an initial diagnosis of lymphoma, in a patient with a prior diagnosis of lymphoma and morphology/immunophenotype available for comparison, FNA/CNB is often sufficient for confirming disease relapse. If enough tissue is obtained on FNA/CNB to perform ancillary studies, a subsequent excisional biopsy is often not needed at the time of initial diagnosis. In these cases, performing an FNA/CNB initially is the best course of action as it saves the patient from a more invasive procedure. Conversely, the patients that require a subsequent biopsy often have a lack of tissue available on the FNA/CNB to perform adequate ancillary testing. The presence of an adequate cell block/core biopsy is imperative for the assessment of hematolymphoid lesions, especially in the assessment of Hodgkin lymphoma or sclerotic lesions as immunohistochemical analysis is paramount given that flow cytometric analysis is often not fruitful because the tissue does not generally aspirate well by FNA.

The type of diagnosis has an impact on the efficacy of FNA/CNB (Table 1). Patients who were diagnosed with DLBCL or HGBCL have a significantly higher rate of diagnostic satisfaction by FNA/CNB (91.0% and 100%, respectively), as compared to the diagnostic rate of small mature B-cell lymphomas (79.2%). This diagnostic difference may be explained by the striking morphologic alteration of the neoplastic cells seen in DLBCL and HGBCL as compared to benign lymphoid cells, while the atypical cells in small mature B-cell lymphomas morphologically demonstrate a resemblance to their benign counterpart. Because FNA/CNB often lose architectural features that are used to evaluate an excisional biopsy, the cytomorphology of the atypical cells becomes of the utmost importance in these limited tissue biopsies. Among the small B-cell lymphomas, follicular lymphoma in particular poses its own set of challenges as it often necessitates histologic grading and growth pattern assessment, which are often precluded on FNA/CNB samples. Therefore, even in cases with an adequate core biopsy demonstrating follicular lymphoma (Image 2), we recommend that a diagnostic comment be included to indicate the possibility of sampling variation. In these cases, it is our practice to suggest that an excisional biopsy be performed for an accurate grading of the follicular lymphoma and assessing the growth pattern if these are clinically important designations. Presumably, CLL and MCL should have demonstrated a higher efficacy of the diagnosis by FNA/CNB because of their characteristic immunophenotype; however, diagnostic advantage is not observed in CLL or MCL in comparison with MZL/LPL in our analysis, probably due to small sample sizes.

In addition to DLBCL and HGBCL, precursor hematolymphoid neoplasms (100%) and plasma cell/plasmablastic neoplasms (100%) have a high rate of diagnostic satisfaction by FNA/CNB due to the homogeneity of the atypical cell population. Conversely, cases of T-cell lymphomas often demonstrate a heterogeneous cell population and do not benefit from FNA/CNB (50.0%) based on this limited analysis. Therefore, a subsequent excisional biopsy should be considered mandatory for the diagnosis and classification of T-cell lymphomas, except in those patients with a prior history of T-cell lymphoma and suspicion for relapse. In addition, lymphomas of B-cell origin become more complicated to assess on FNA/CNB as the background reactive T cells become more prominent. For example, T-cell/histiocyte rich LBCL, NLPHL with T-cell–rich nodular pattern or T-cell–rich diffuse pattern, cHL with rare Reed-Sternberg–like cells, and small B-cell lymphoma with prominent T-cell reaction may be diagnostic pitfalls. In cases with a predominant T-cell infiltrate on FNA/CNB, an underlying B-cell neoplasm may be masked (Image 6) and a subsequent excisional biopsy is required to accurately characterize the lesion.

There are a few pitfalls in the evaluation of hematolymphoid lesions using FNA/CNB. Certain lymphoid lesions have a heterogeneous distribution of neoplastic and reactive components, with varying morphology. Due to its small size, an FNA/CNB cannot provide a panoramic view of the architectural changes, and therefore may result in an incorrect diagnosis if focal morphologic findings are misleading. Below are a few examples of pitfalls identified on FNA/CNB as compared to excisional biopsy.

Mistaken diagnosis of T-cell lymphoma on CNB, whereas diagnosed as small B-cell lymphoma with intense T-cell infiltrate on excisional biopsy (case 2 in Table 2; Image 6).

Incorrect diagnosis of T-cell lymphoma on FNA, with subsequent diagnosis of cHL with only rare to absent Reed-Sternberg cells on the excisional biopsy (case 5 in Table 2; Supplemental Image 1).

Other authors have described examples in which a diagnosis of T-cell lymphoma could be considered in cases of NLPHL. This can be a particular pitfall in the T-cell–rich nodular pattern or diffuse, T-cell–rich pattern of NLPHL due to the predominance of T cells, which may be atypical in morphology and T-follicular helper phenotye.29

Previous studies have described cases in which a diagnosis of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) may incorrectly be classified as EBV-positive DLBCL. This diagnostic challenge was noted particularly when an adequate cell block/core biopsy was not available for a full immunohistochemical evaluation.30,31

Other investigators have noted that AITL may be confused for a plasmacytic neoplasm on limited biopsy. Rare cases of AITL may exhibit clonal plasmacytosis that could lead to the misdiagnosis of plasma cell neoplasm or B-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation on FNA/CNB evaluation.32,33

Overlooking DLBCL in a case of follicular lymphoma with focal histologic transformation due to sampling error (case 4 in Table 2).

Overlooking EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder due to a polymorphic lymphoid population (case 1 in Table 2).

Overlooking one of the neoplastic components in composite lymphomas (case 3 in Table 2).

The caveats for FNA/CNB evaluation of hematolymphoid lesions are listed below.

Always include flow cytometric analysis and a cell block/core biopsy in the FNA/CNB of an enlarged lymph node or other lesion suspicious for a hematolymphoid lesion. This should be applied not only to the cases without a previous history of hematolymphoid neoplasm but also to those suspected for disease relapse because histologic transformation or a new de novo disease process must be excluded. The level of diagnostic confidence of an FNA/CNB evaluation is enhanced with both flow cytometry and cell block/needle core in comparison with either alone, particularly because more than one neoplastic component may be detected by flow cytometry, while this second component is often overlooked on morphologic assessment.

The diagnostic efficacy of FNA/CNB is high in patients with history of hematolymphoid neoplasm and suspicion for a persistence, progression, or relapse of the disease.

Higher efficacy of FNA/CNB can be achieved in cases of hematolymphoid neoplasms with homogenous cytomorphology, aggressive histology, and/or characteristic immunophenotype, such as DLBCL, HGBCL, plasma cell neoplasm, hematolymphoid precursor neoplasm, etc.

If T-cell lymphoma is the favored diagnosis on FNA/CNB, an excisional biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. The only exceptions are if the neoplastic cells are homogenously abnormal (ie, enlarged, anaplastic), are detected by flow cytometric analysis, or if the patient has history of T-cell lymphoma and the histologic features on FNA/CNB are similar to those identified on the previous diagnostic biopsy.

An excisional biopsy should be recommended in every case demonstrating a polymorphic infiltrate including mixed small to large-sized B cells with many T cells. A polymorphic inflammatory cell infiltrate on FNA/CNB could be seen in several different lymphoproliferative disorders, including EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma, AILT, MZL, or other small mature B-cell lymphomas with an intense T-cell reaction, in addition to cHL and mature T-cell lymphoma.

Small B-cell lymphomas with a nonspecific immunophenotypic profile, such as MZL and LPL, should be cautiously evaluated on FNA/CNB. An additional tissue biopsy should be suggested to confirm the diagnosis as needed given the lack of a clear diagnostic immunophenotype.

Clonal plasmacytosis can be seen in rare cases of plasma cell variant of Castleman lymphadenopathy and AITL. Therefore, the diagnosis of plasma cell neoplasm should not be made on FNA/CNB simply based on light chain restriction without associated abnormal plasma cell morphology or an aberrant immunophenotype (ie, CD56, CD117, or cyclin D1 expression).

Follicular lymphoma poses a diagnostic challenge to the assessment using FNA/CNB because histologic grading and growth pattern determination is not accurate using small biopsy samples. Sampling variation may occur, resulting in occasional underestimation of histologic grade; additionally, areas of transformation to DLBCL may be overlooked on the FNA/CNB.

Conclusions

FNA/CNB is a simple, minimally invasive diagnostic procedure, and it is practical in the diagnosis of hematolymphoid neoplasms with approximately 80% of the procedures resulting in diagnosis without the need for a subsequent excisional biopsy. FNA/CNB is particularly effective in patients with a prior history of lymphoma or other hematolymphoid neoplasm in which the goal is to confirm the presence of residual disease after treatment or to evaluate for disease relapse. The diagnostic accuracy depends on the diagnosis, with a higher diagnostic rate identified in DLBCL, HGBCL, plasma cell neoplasm, and precursor hematolymphoid malignancies. If a cell block/core biopsy is obtained and yields sufficient tissue for ancillary testing, FNA/CNB is more likely to render an accurate diagnosis. However, the use of FNA/CNB in evaluating hematolymphoid lesions has a few potential pitfalls. These diagnostic challenges include T-cell lymphomas, lymphoma of B-cell origin with a prominent T-cell infiltrate, cHL with rare Reed-Sternberg cells, polymorphic EBV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, histologic grading and growth pattern identification in follicular lymphoma, and composite lymphomas. As a pathologist, it is imperative to understand the limitations of FNA/CNB so that an excisional biopsy can be recommended in the appropriate situations to avoid misdiagnosis and mistreatment.

This project was presented in part at the 108th Annual Meeting of United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology; March 16-21, 2019; National Harbor, MD.