-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mary Quattlebaum, Dawn K Wilson, Timothy Simmons, Pamela P Martin, Systematic review of family-based interventions integrating cultural and family resilience components to improve Black adolescent health outcomes, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, Volume 59, Issue 1, 2025, kaae079, https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaae079

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Past reviews have shown that culturally salient resilience interventions buffer the negative effects of racial discrimination on psychological and behavioral outcomes among Black youth. However, these prior reviews neglect to integrate trials targeting physical health and/or health-promoting outcomes, synthesize trials based on methodological rigor, or systematically assess efficacy or resilience intervention components.

This systematic review expands on past research by (1) providing an up to-date literature review on family-based cultural resilience interventions across a range of health-related outcomes (physical health, health behaviors, health risk-taking behaviors, and psychological), (2) evaluating the rigor of these interventions, (3) analyzing the efficacy of rigorous interventions, and (4) describing the resilience intervention components of rigorous interventions.

Using the PRISMA guidelines, a systematic search was conducted from 1992 to 2022. Studies were included if they were family-based resilience interventions targeting health-related outcomes among Black adolescents ages 10-17 years.

Fifteen studies met inclusion criteria, 10 of which were not included in past reviews. Overall, 10 trials demonstrated high methodological rigor, 9 of which were efficacious. Most rigorous, efficacious trials targeted health risk-taking behaviors outcomes (~66%), whereas none targeted health promotion behaviors (physical activity, diet). Resilience components of rigorous efficacious interventions included racial socialization (racial coping, cultural pride) and family resilience (communication, routine), with fewer integrating racial identity (self-concept, role models) and cultural assets (spirituality, communalism).

These findings suggest the need to replicate existing rigorous strengths-based resilience interventions and address broader outcomes, including health-promoting behaviors, in the future.

Lay Summary

Growing evidence suggests that strengths-based cultural and family resilience interventions may buffer the negative impacts of discrimination and promote positive health-related outcomes in Black adolescents and families. However, only 3 systematic reviews have been conducted and these prior reviews are limited in scope. The current systematic review aimed to expand on prior reviews by (1) providing an up to-date literature review on family-based cultural resilience interventions across a range of health-related outcomes (physical health, health behaviors, health risk-taking behaviors, and psychological), (2) evaluating the rigor of these interventions, (3) analyzing the efficacy of rigorous interventions, and (4) describing the resilience intervention components of rigorous interventions. We conducted a systematic search of relevant studies published between 1992 and 2022 and identified eligible studies using a comprehensive study screening process. Fifteen studies were eligible and included in this review. Ten of these trials had high methodological rigor, with 9 showing intervention efficacy, suggesting initial support for such trials. Many of these rigorous, efficacious trials targeted health risk-taking behavior outcomes but none targeted health promotion behaviors. Regarding resilience intervention components, rigorous efficacious trials included racial socialization and family resilience resources, but fewer of these trials integrated racial identity or cultural assets.

Introduction

Racial discrimination, which is characterized as differential treatment by individuals and social institutions based on one’s racial group, is recognized as the most prominent stressor for Black adolescents and their families.1,2 Exposure to such discrimination can contribute to poor physical, behavioral, psychological, and social outcomes among Black adolescents. Specifically, racial discrimination has been linked to poor health behaviors (physical inactivity, poor diet), health risk-taking behaviors (elevated substance use, risky sexual behaviors), and poor health-related outcomes (eg, elevated body mass index, elevated inflammation).3,4 Exposure to discrimination has also been associated with poor psychological outcomes, such as increased depression and anxiety5,6 and high parent-youth conflict7 among Black adolescents and families. Given the consequences of discrimination on a range of physical, behavioral, psychological, and social outcomes, there is a pressing need to identify relevant protective factors that may buffer the impact of these stressors and promote positive outcomes among Black adolescents and their families.

Growing evidence suggests that leveraging strengths-based resilience resources inherently rooted within Black families and their culture/traditions may be an important point of intervention to buffer the consequences of discrimination and promote resilience for improving health-related outcomes in adolescents.8–10 Velma Murry’s Integrated Stress Model for Black Americans, as well as Masten’s Resilience Theory,11,12 propose that resilience resources are salient strengths-based protective factors that can be cultivated through cultural and familial resources to build adolescent and family capacity to rebound and adapt in response to extreme stress and adversity, including racial discrimination. In line with these frameworks, 4 core resilience resources have been shown to be particularly salient to Black families, including racial socialization (ie, family messages and/or practices related to cultural pride and racial coping skills), racial identity (ie, importance/meaning that an individual holds for their racial group), cultural assets (eg, spirituality, extended kinship, communalism, and optimism/positivity), and family resilience (eg, coping skills, positive communication, social support, family routines/rituals).8,12–15 Specifically, Murry12 purports that these cultural resources (racial socialization, racial identity, cultural assets) cultivate family resilience, which then buffers environmental stressors (racial stress, inequity) and contributes to positive health-related outcomes (eg, psychological, social, health). In addition to this indirect pathway, Murry12 argues that these cultural resilience resources directly contribute to such positive outcomes. While prior trials integrating positive parenting have been shown to promote positive health-related outcomes,16 Masten11 also argues to expand beyond positive parenting and further build family resilience through family support, coping, and routines to promote positive health-related outcomes. These resilience resources emphasize the importance of understanding Black families through a strengths-based framework to buffer racial stress and promote positive health-related outcomes.

To the best of our knowledge, only 3 previous systematic reviews have synthesized interventions integrating these resilience resources.9,17,18 A prior review conducted by Metzger et al.17 assessed prevention programs for Black adolescents (10-18 years old) that incorporated 3 of the four resilience resources (racial identity, cultural assets, racial socialization) to improve health risk-taking behavior outcomes (eg, substance use, violence, risky sexual behavior). Jones and Neblett18 also conducted a review that assessed trials integrating 3 protective factors (racial identity, cultural assets, racial socialization) that targeted a variety of outcomes (eg, health risk-taking behaviors, psychological, academic) among Black youth (9-19 years old). Another review by Neblett9 examined resilience trials integrating racial identity, racial socialization, cultural assets, and family resilience that targeted psychological well-being and health risk-taking behaviors. Although these past reviews make important contributions to the field, there are notable gaps. Specifically, none of these reviews included trials targeting physical health or health-promoting outcomes, synthesized trials based on methodological rigor, or systematically analyzed trial efficacy. Further, 2 of these reviews did not include trials that integrated family resilience as an intervention component.17,18 These limitations of past reviews hinder our ability to draw takeaways to inform future resilience interventions.

The increasing emphasis on strengths-based resilience resources salient to Black families in recent literature10,12 necessitates that future reviews include a comprehensive overview of all trials conducted to-date. Considering the consequences of discrimination on physical health outcomes,3,4 broadening the scope of reviews to analyze existing resilience trials that target physical health or health-promoting outcomes is warranted. Further, evaluating and synthesizing trials with strong methodological rigor is essential to cultivate informed recommendations for future research. It is also critical to systematically analyze intervention efficacy to establish more confidence and understanding of past findings. Thus, the purpose of this systematic review was to (1) provide an up to-date literature review of family-based cultural resilience interventions across a range of health-related outcomes (physical health, health behaviors, health risk-taking behaviors, psychological), (2) evaluate the rigor of these interventions, (3) systematically analyze the efficacy of rigorous interventions, and (4) describe the resilience intervention components of these efficacious interventions.

Methods

Search strategy

The current review followed the PRISMA guidelines and was preregistered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROPSERO). Consistent with past reviews and consultation with university library services, the following online journal databases were searched: PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Gray literature, including thesis and dissertation articles, was searched using Web of Science. An a priori-defined search string with key terms was developed by reviewing search terms used in relevant intervention studies and studies focused on relevant resilience components, identifying MeSH terms, and utilizing database thesauruses. Existing reviews and meta-analyses, reference lists, and additional searches using key words from the search string were also reviewed to identify relevant articles for the current review. Databases were searched by the research team in 2023.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies had to meet several outlined criteria to be included in the current review. The a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria followed a PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study type) framework19 (See the Supplemental file). Specifically, the target population was confined to Black adolescents aged between 10 and 17 years old and their parent/guardian. This age range was selected given that adolescence is a critical vulnerability period in which health-related behaviors and psychological well-being are shaped and is a prominent phase of growth in independence and self-regulation, all of which have long-lasting impacts on trajectories into adulthood.20 Studies were only included if 100% of the sample identified as Black. For the study design, articles were included if they were intervention studies with or without a comparison or control group, such as quasi-experimental trials (nonrandomized), experimental trials, pilot trials, or randomized controlled trials (RCT). Interventions were required to be family-based; thus, studies were excluded if a parent or guardian was not actively integrated into the intervention. Interventions were only included if they utilized resilience-based frameworks with cultural and family resilience components. Interventions had to primarily target at least one of the following outcomes: health-related outcomes such as physical health (blood pressure, obesity, inflammation), health promotion behaviors (physical activity, dietary intake), and health risk-taking behaviors (substance use, unprotected sex, violence) or psychological outcomes (self-esteem, self-pride, depression, anxiety, family cohesion). If a research team delivered a similar intervention program but examined different target outcomes, assessment timepoints, and/or participant inclusion criteria and published these findings separately, papers were included as distinct studies. Supplementary Table S1 indicated the intervention program delivered in each study. Studies were only included if they were published within the last 30 years (1992-2022). This timeframe was set as this is approximately the timeframe in which interventions integrating cultural and family resilience components among Black youth was increasingly emphasized as critical in literature.15

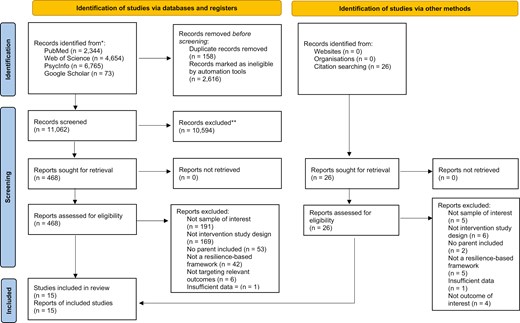

Study screening

A flow chart based on PRISMA guidelines is provided to outline the process of study selection and extraction (Figure 1). The Rayyan online platform was utilized to aid in study screening. Study screening was conducted by 2 independent raters. The initial screening of titles was conducted by Independent Rater 1 according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that met initial criteria were then assessed based on study title and abstract by Independent Rater 1 and a random 30% were screened by Independent Rater 2. The reviewers established an agreement of 0.70. Discrepancies were resolved by a third rater to reach an agreement of 100%. The remaining studies were then screened based on the full-text by Independent Raters 1 and 2.

Search results across all 4 databases produced 13,836 articles. Upon removing duplicates, there were a total of 11,062 articles remaining. An initial screening of titles was conducted to determine potentially relevant articles based on inclusion/exclusion criteria and 10,594 were deemed ineligible. Title and abstracts were screened for the remaining 468 articles. Full-text articles of relevant studies were pulled to confirm if they met all aspects of inclusion criteria, resulting in 11 eligible articles. Upon examining relevant reviews, meta-analyses, and reference sections, an additional 4 articles were identified as eligible articles. Thus, the current review includes a total of 15 articles.

Study rigor

The current review evaluated the methodology of these 15 studies to demonstrate the rigor of the interventions. In line with prior reviews and relevant literature,21–25 methodological rigor was assessed by determining if studies met the following criteria: sample randomization, use of comparison or control group, defined problem or population, use of validated/reliable outcome measures, use of treatment manual/curriculum, large sample size (25 + participants per group), and a standardized approach to manage missing data (eg, intention-to-treat analysis). Studies then received a methodological rigor score based on the number of criteria that were met resulting in a rigor label ranging from Weak to Very Strong. Specifically, studies that met all criteria (0 weak domains) were assigned as Very Strong rigor, studies that met almost all criteria (1 weak domain) were assigned as Strong rigor, studies that met some criteria (2-3 weak domains) were assigned as Moderate rigor, and studies that met very few criteria (4 or more weak domains) were assigned as Weak rigor. Rigor of the studies selected for the review was independently assessed by Independent Rater 1 and 2. The reviewers established an agreement of 0.70. Discrepancies were resolved by a third rater to reach an agreement of 100%.

Study efficacy

Study efficacy of the trials was determined using 3 parameters that have been well-established in prior literature.26,27 Specifically, trials were analyzed to determine if: (1) there was a significant change in the target health-related outcome from pre-post or from pre-post compared to the control group (if applicable) based on an a priori p-value, (2) the effects were in the expected direction, (3) and if an effect size was provided. If the trial met the first 2 parameters, studies were deemed efficacious, and trials that provided an effect size allowed for more evidence of the strength of intervention efficacy. Table 2 outlines which of these study efficacy parameters were met and includes the p-value of intervention effects. If an efficacious trial assessed potential mechanisms of outcomes, these were noted in Table 2. If the intervention included multiple outcomes that met inclusion criteria for the current review, findings of both outcomes were synthesized. Secondary outcomes that were not included in the current study’s inclusion criteria were not discussed.

Results

The first aim of this review was to provide an up to-date review of the literature base. Following the PRISMA flowchart, the final review included 15 total studies (Figure 1). Of these 15 studies, 10 studies have not been analyzed in prior reviews. These 10 new studies were conducted between 1996 and 2019, suggesting that some trials have been conducted since prior reviews were published and some trials were simply missed in prior reviews. All the studies were published in peer-reviewed journals, as no gray literature met inclusion criteria. Across the studies, participant ethnicity was predominantly African American (~87%), with the remaining studies including participants of Caribbean descent (~7%) or no reported participant ethnicity (~7%). Several studies (40%) included samples in which the majority identified as low-income. Four studies shared overlapping intervention programs; however, these studies targeted distinct outcomes, assessment timepoints, and/or participant inclusion criteria (eg, mothers only vs. mothers and fathers) and thus were analyzed separately in the current review.28–31 Two other studies shared overlapping intervention programs but targeted distinct outcomes and were also analyzed separately in this review.32,33

Rigor

The second aim of this review was to evaluate the rigor of trials included in this review (Table 1). Of the 15 studies, ~60% (9 studies) fell in the Very Strong methodological rigor range, ~7% fell in the Strong range (1 study), ~7% (1 study) fell in the Moderate rigor range, and ~27% (4 studies) fell in the Weak rigor range. The study design of the 15 articles showed variability, with 3 studies (20%) identified as RCTs, 4 studies (~27%) identified as randomized trials with a control group, 1 study (~7%) identified as cluster randomized trial, 2 studies (~13%) randomized attention-controlled trial, 4 studies (~27%) nonrandomized with no control group, and 1 study (~7%) nonrandomized with a control group. Studies in the Weak rigor range primarily received the score due to a small sample size, not utilizing a structured approach to handle missing data, not utilizing a comparison group, or not randomizing participants. Overall, 10 studies fell in the Very Strong and Strong range and thus were considered highly rigorous. Of these highly rigorous studies, 6 of these have not been included in previous reviews.29,30,32–35 Studies falling in the Moderate and Weak methodological range were excluded from the text and tables due to the lack of rigor.36–39

| Author, year . | Randomized . | Comparison treatment . | Defined population and/or problem . | Valid, reliable outcome measures . | Treatment manual or curriculum . | 25+ participants per group . | Intention-to-Treat analysis or structured approach to manage missing data . | Overall score (# of weak domains) . | Rigor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aronowitz et al., 2015 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Bartlett and Shelton, 2010 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Brody et al., 2010 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Flay et al., 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Harvey and Hill, 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | M | ||

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Miller et al., 2014 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 1 | S | |

| Watson et al., 2015 | X | 6 | W | ||||||

| Whaley and McQueen, 2004 | X | X | 5 | W |

| Author, year . | Randomized . | Comparison treatment . | Defined population and/or problem . | Valid, reliable outcome measures . | Treatment manual or curriculum . | 25+ participants per group . | Intention-to-Treat analysis or structured approach to manage missing data . | Overall score (# of weak domains) . | Rigor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aronowitz et al., 2015 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Bartlett and Shelton, 2010 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Brody et al., 2010 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Flay et al., 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Harvey and Hill, 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | M | ||

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Miller et al., 2014 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 1 | S | |

| Watson et al., 2015 | X | 6 | W | ||||||

| Whaley and McQueen, 2004 | X | X | 5 | W |

Overall Score: VS = 0 weak domains; S = 1 weak domain; M = 2–3 weak domains; W = 4 or more weak domain. Lower rigor scores demonstrate increased rigor.

Abbreviations: M, Moderate; S, Strong; VS, Very Strong; W, Weak.

| Author, year . | Randomized . | Comparison treatment . | Defined population and/or problem . | Valid, reliable outcome measures . | Treatment manual or curriculum . | 25+ participants per group . | Intention-to-Treat analysis or structured approach to manage missing data . | Overall score (# of weak domains) . | Rigor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aronowitz et al., 2015 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Bartlett and Shelton, 2010 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Brody et al., 2010 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Flay et al., 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Harvey and Hill, 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | M | ||

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Miller et al., 2014 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 1 | S | |

| Watson et al., 2015 | X | 6 | W | ||||||

| Whaley and McQueen, 2004 | X | X | 5 | W |

| Author, year . | Randomized . | Comparison treatment . | Defined population and/or problem . | Valid, reliable outcome measures . | Treatment manual or curriculum . | 25+ participants per group . | Intention-to-Treat analysis or structured approach to manage missing data . | Overall score (# of weak domains) . | Rigor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aronowitz et al., 2015 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Bartlett and Shelton, 2010 | X | X | X | 4 | W | ||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Brody et al., 2010 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Flay et al., 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Harvey and Hill, 2004 | X | X | X | X | X | 2 | M | ||

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Miller et al., 2014 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Murry et al., 2019 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0 | VS |

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 1 | S | |

| Watson et al., 2015 | X | 6 | W | ||||||

| Whaley and McQueen, 2004 | X | X | 5 | W |

Overall Score: VS = 0 weak domains; S = 1 weak domain; M = 2–3 weak domains; W = 4 or more weak domain. Lower rigor scores demonstrate increased rigor.

Abbreviations: M, Moderate; S, Strong; VS, Very Strong; W, Weak.

Range of outcomes

Of the 10 highly rigorous studies, there was a diverse range of intervention outcomes, including health risk-taking behaviors, psychological, and physical health outcomes. Specifically, 6 of these studies targeted solely health risk-taking behaviors (substance use, sexual behavior, and delinquency),28,32,34,35,40,41 2 studies targeted psychological outcomes (self-pride and self-concept),30,33 1 study targeted both health risk-taking behaviors and psychological outcomes,31 and 1 study targeted physical health outcomes (inflammation scores).29 Across all interventions identified for this review, none targeted health promotion behaviors (eg, physical activity, diet), demonstrating a major gap in the extant literature.

Efficacy

The third aim of this review was to systematically assess and summarize the efficacy of highly rigorous trials. A detailed summary of study findings of rigorous trials are provided in Table 2. Nine of the 10 highly rigorous studies (90%) were efficacious based on the pre-determined efficacy parameters. Five of these trials demonstrated significant intervention effects on health risk-taking behaviors, including significant reductions in the frequency of unprotected sex substance use, sexual behavior, externalizing behaviors (violent and provoking behavior, drug/alcohol use, delinquency, sexual intercourse), and significant increases in condom efficacy among intervention youth compared to control youth.28,32,34,35,40 Moreover, one of these trials showed a large effect size (d = 0.82)40 and another trial showed a trending decline in risky behaviors at long-term follow-up (~22 months post-treatment),35 which is promising for demonstrating efficacy and sustained change. Two trials showed significant intervention effects on psychological outcomes, including improved youth self-pride (self-esteem, racial identity) and sexual self-concept (positive body image, sexual social comparison).30,33 One trial showed significant intervention effects on both psychological and health risk-taking behaviors, including increased adaptive parenting skills and youth self-pride, which indirectly improved sexual risk intention and behavior (d = 0.49).31 The only study targeting physical health outcomes showed significant reductions in inflammation composite scores at long-term follow-up (8 years post-treatment) among intervention youth compared to youth in the control group with a large effect size (d = −0.90).29

| Author, year . | Study sample . | Study design, assessment timepoints, and targeted outcome . | Efficacy . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant pre/Post change . | Expected direction . | Effect size (Cohen’s d) . | |||

| Very strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 332 dyads); 53.6% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: Efficacy trial Assessment: Pre-txt/3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Regulated-communicative parenting | Youth findings: Intervention youth demonstrated lower reports of risky behavior compared to control youth (P < .05) and youth-reported targeted parenting compared to control youth (P < .05). Parent findings: Intervention families also showed increased regulated-communicative parenting (P < .01). | Y | N |

| Brody et al., 2010 | Youth 17 y/o and their parent (N = 347 dyads); 58.5% youth female; Ethnicity: AA Income: 42% of pts lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 7-mos. after post-txt, long-term follow-up (~17 mos. after pre-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly lower levels of risky behavior [eg, substance use, sexual behavior] (independent of life stress levels) compared to the control group at long-term follow-up (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Flay et al., 2004 | Youth in 5th grade (M age = 10.8+/−0.6) and their parents (N = 1155 dyads) 49.5% male youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 77% of pts received federally subsidized school lunch Metropolitan Chicago, IL (school-based) | Design: Cluster randomized trial [Social Development Curriculum (SDC), School/Community Intervention (SCI), Health Enhancement control curriculum (HEC)] Assessment: Pre/post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Males in SCI had significantly lower engagement in problem behaviors (violence, provoking behavior, school delinquency, substance use, sexual intercourse, condom use) than males in HEC (P-values ranged < 0.001-0.05) Males in SDC had marginally lower engagement in problem behaviors than males in HEC (P-values ranged 0.05-0.08) No significant effects were shown with females (P > .05) | Y | Y; d = 0.52 (SDC); d = 0.82 (SCI) |

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% youth female Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological | Intervention families demonstrated increased protective family management skills [parent-child communication, problem-solving] compared to the control group at 2-months post-txt (P = .023) | Y | N |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated decreased frequency of unprotected sex (P < .01) and increased condom efficacy (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Miller et al., 2014 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 272 dyads); 57% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: 8 years post-txt Outcome: Physical health Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly reduced inflammation composite scores compared to control group youth (P < .001). | Y | Y; d = −0.90 |

| Murry et al., 2005 | Youth 11 y/o and their mother (N = 332 dyads); 54% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 46.3% of pts. lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families showed greater changes in targeted parenting skills than the control group at 3-mos. post-txt (P < .01). Positive changes in youth’s self-pride and sexual self-concept at post-txt was directly and indirectly impacted by improved parenting skills | Y | N |

| Murry et al., 2007 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 284 dyads); ~50% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: ~40% received public assistance Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt, long-term follow-up (29 mos. post-txt) Outcomes: Psychological; Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families demonstrated increased adaptive parenting skills at 3-mos. post-txt compared to the control group (P < .01). Increased adaptive parenting skills contributed to increased youth self-pride at 29-month follow-up (P < .01), which indirectly improved peer orientation, sexual risk intention and behavior (P < .01). | Y | Y; d = 0.49 |

| Murry et al., 2019 | Youth (6th grade) aged M = 11.4 y/o and their parents (N = 421 dyads); 54% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 14% of pts. received public assistance Rural counties in TN | Design: Three-arm RCT Assessment: Pre/post-txt, long-term follow-up (~22 mos. post-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting | Youth findings: Tech-based youth showed a significant decrease in risky behavior engagement intention at post-txt (P = .04) and a decrease in risky behavior engagement at long-term follow-up (P = .04). Group-based youth demonstrated a significant increase in deviant peer affiliation at post-txt (P = .002) and a non-significant reduction in risky behavior at long-term follow-up (P = .58). Parent findings: Tech-based families showed significant improvements in parenting specific to sensitive topics (P = .03). Group-based families demonstrated significant increases in supportive parenting (P = .02). | Y (for tech youth) | N |

| Strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | Youth 12-16 y/o and their parent (N = 260 dyads); 100% male youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 50% received free or reduced lunch Durham, NC | Design: Random assignment trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 18-mos. post-txt, 30-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | No significant pre/post change (P > .05). | – | – |

| Author, year . | Study sample . | Study design, assessment timepoints, and targeted outcome . | Efficacy . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant pre/Post change . | Expected direction . | Effect size (Cohen’s d) . | |||

| Very strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 332 dyads); 53.6% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: Efficacy trial Assessment: Pre-txt/3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Regulated-communicative parenting | Youth findings: Intervention youth demonstrated lower reports of risky behavior compared to control youth (P < .05) and youth-reported targeted parenting compared to control youth (P < .05). Parent findings: Intervention families also showed increased regulated-communicative parenting (P < .01). | Y | N |

| Brody et al., 2010 | Youth 17 y/o and their parent (N = 347 dyads); 58.5% youth female; Ethnicity: AA Income: 42% of pts lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 7-mos. after post-txt, long-term follow-up (~17 mos. after pre-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly lower levels of risky behavior [eg, substance use, sexual behavior] (independent of life stress levels) compared to the control group at long-term follow-up (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Flay et al., 2004 | Youth in 5th grade (M age = 10.8+/−0.6) and their parents (N = 1155 dyads) 49.5% male youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 77% of pts received federally subsidized school lunch Metropolitan Chicago, IL (school-based) | Design: Cluster randomized trial [Social Development Curriculum (SDC), School/Community Intervention (SCI), Health Enhancement control curriculum (HEC)] Assessment: Pre/post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Males in SCI had significantly lower engagement in problem behaviors (violence, provoking behavior, school delinquency, substance use, sexual intercourse, condom use) than males in HEC (P-values ranged < 0.001-0.05) Males in SDC had marginally lower engagement in problem behaviors than males in HEC (P-values ranged 0.05-0.08) No significant effects were shown with females (P > .05) | Y | Y; d = 0.52 (SDC); d = 0.82 (SCI) |

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% youth female Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological | Intervention families demonstrated increased protective family management skills [parent-child communication, problem-solving] compared to the control group at 2-months post-txt (P = .023) | Y | N |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated decreased frequency of unprotected sex (P < .01) and increased condom efficacy (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Miller et al., 2014 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 272 dyads); 57% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: 8 years post-txt Outcome: Physical health Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly reduced inflammation composite scores compared to control group youth (P < .001). | Y | Y; d = −0.90 |

| Murry et al., 2005 | Youth 11 y/o and their mother (N = 332 dyads); 54% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 46.3% of pts. lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families showed greater changes in targeted parenting skills than the control group at 3-mos. post-txt (P < .01). Positive changes in youth’s self-pride and sexual self-concept at post-txt was directly and indirectly impacted by improved parenting skills | Y | N |

| Murry et al., 2007 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 284 dyads); ~50% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: ~40% received public assistance Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt, long-term follow-up (29 mos. post-txt) Outcomes: Psychological; Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families demonstrated increased adaptive parenting skills at 3-mos. post-txt compared to the control group (P < .01). Increased adaptive parenting skills contributed to increased youth self-pride at 29-month follow-up (P < .01), which indirectly improved peer orientation, sexual risk intention and behavior (P < .01). | Y | Y; d = 0.49 |

| Murry et al., 2019 | Youth (6th grade) aged M = 11.4 y/o and their parents (N = 421 dyads); 54% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 14% of pts. received public assistance Rural counties in TN | Design: Three-arm RCT Assessment: Pre/post-txt, long-term follow-up (~22 mos. post-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting | Youth findings: Tech-based youth showed a significant decrease in risky behavior engagement intention at post-txt (P = .04) and a decrease in risky behavior engagement at long-term follow-up (P = .04). Group-based youth demonstrated a significant increase in deviant peer affiliation at post-txt (P = .002) and a non-significant reduction in risky behavior at long-term follow-up (P = .58). Parent findings: Tech-based families showed significant improvements in parenting specific to sensitive topics (P = .03). Group-based families demonstrated significant increases in supportive parenting (P = .02). | Y (for tech youth) | N |

| Strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | Youth 12-16 y/o and their parent (N = 260 dyads); 100% male youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 50% received free or reduced lunch Durham, NC | Design: Random assignment trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 18-mos. post-txt, 30-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | No significant pre/post change (P > .05). | – | – |

Abbreviations: AA, African American; N, No; Y, Yes.

| Author, year . | Study sample . | Study design, assessment timepoints, and targeted outcome . | Efficacy . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant pre/Post change . | Expected direction . | Effect size (Cohen’s d) . | |||

| Very strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 332 dyads); 53.6% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: Efficacy trial Assessment: Pre-txt/3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Regulated-communicative parenting | Youth findings: Intervention youth demonstrated lower reports of risky behavior compared to control youth (P < .05) and youth-reported targeted parenting compared to control youth (P < .05). Parent findings: Intervention families also showed increased regulated-communicative parenting (P < .01). | Y | N |

| Brody et al., 2010 | Youth 17 y/o and their parent (N = 347 dyads); 58.5% youth female; Ethnicity: AA Income: 42% of pts lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 7-mos. after post-txt, long-term follow-up (~17 mos. after pre-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly lower levels of risky behavior [eg, substance use, sexual behavior] (independent of life stress levels) compared to the control group at long-term follow-up (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Flay et al., 2004 | Youth in 5th grade (M age = 10.8+/−0.6) and their parents (N = 1155 dyads) 49.5% male youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 77% of pts received federally subsidized school lunch Metropolitan Chicago, IL (school-based) | Design: Cluster randomized trial [Social Development Curriculum (SDC), School/Community Intervention (SCI), Health Enhancement control curriculum (HEC)] Assessment: Pre/post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Males in SCI had significantly lower engagement in problem behaviors (violence, provoking behavior, school delinquency, substance use, sexual intercourse, condom use) than males in HEC (P-values ranged < 0.001-0.05) Males in SDC had marginally lower engagement in problem behaviors than males in HEC (P-values ranged 0.05-0.08) No significant effects were shown with females (P > .05) | Y | Y; d = 0.52 (SDC); d = 0.82 (SCI) |

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% youth female Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological | Intervention families demonstrated increased protective family management skills [parent-child communication, problem-solving] compared to the control group at 2-months post-txt (P = .023) | Y | N |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated decreased frequency of unprotected sex (P < .01) and increased condom efficacy (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Miller et al., 2014 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 272 dyads); 57% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: 8 years post-txt Outcome: Physical health Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly reduced inflammation composite scores compared to control group youth (P < .001). | Y | Y; d = −0.90 |

| Murry et al., 2005 | Youth 11 y/o and their mother (N = 332 dyads); 54% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 46.3% of pts. lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families showed greater changes in targeted parenting skills than the control group at 3-mos. post-txt (P < .01). Positive changes in youth’s self-pride and sexual self-concept at post-txt was directly and indirectly impacted by improved parenting skills | Y | N |

| Murry et al., 2007 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 284 dyads); ~50% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: ~40% received public assistance Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt, long-term follow-up (29 mos. post-txt) Outcomes: Psychological; Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families demonstrated increased adaptive parenting skills at 3-mos. post-txt compared to the control group (P < .01). Increased adaptive parenting skills contributed to increased youth self-pride at 29-month follow-up (P < .01), which indirectly improved peer orientation, sexual risk intention and behavior (P < .01). | Y | Y; d = 0.49 |

| Murry et al., 2019 | Youth (6th grade) aged M = 11.4 y/o and their parents (N = 421 dyads); 54% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 14% of pts. received public assistance Rural counties in TN | Design: Three-arm RCT Assessment: Pre/post-txt, long-term follow-up (~22 mos. post-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting | Youth findings: Tech-based youth showed a significant decrease in risky behavior engagement intention at post-txt (P = .04) and a decrease in risky behavior engagement at long-term follow-up (P = .04). Group-based youth demonstrated a significant increase in deviant peer affiliation at post-txt (P = .002) and a non-significant reduction in risky behavior at long-term follow-up (P = .58). Parent findings: Tech-based families showed significant improvements in parenting specific to sensitive topics (P = .03). Group-based families demonstrated significant increases in supportive parenting (P = .02). | Y (for tech youth) | N |

| Strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | Youth 12-16 y/o and their parent (N = 260 dyads); 100% male youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 50% received free or reduced lunch Durham, NC | Design: Random assignment trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 18-mos. post-txt, 30-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | No significant pre/post change (P > .05). | – | – |

| Author, year . | Study sample . | Study design, assessment timepoints, and targeted outcome . | Efficacy . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant pre/Post change . | Expected direction . | Effect size (Cohen’s d) . | |||

| Very strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Brody et al., 2006 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 332 dyads); 53.6% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: Efficacy trial Assessment: Pre-txt/3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Regulated-communicative parenting | Youth findings: Intervention youth demonstrated lower reports of risky behavior compared to control youth (P < .05) and youth-reported targeted parenting compared to control youth (P < .05). Parent findings: Intervention families also showed increased regulated-communicative parenting (P < .01). | Y | N |

| Brody et al., 2010 | Youth 17 y/o and their parent (N = 347 dyads); 58.5% youth female; Ethnicity: AA Income: 42% of pts lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 7-mos. after post-txt, long-term follow-up (~17 mos. after pre-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly lower levels of risky behavior [eg, substance use, sexual behavior] (independent of life stress levels) compared to the control group at long-term follow-up (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Flay et al., 2004 | Youth in 5th grade (M age = 10.8+/−0.6) and their parents (N = 1155 dyads) 49.5% male youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 77% of pts received federally subsidized school lunch Metropolitan Chicago, IL (school-based) | Design: Cluster randomized trial [Social Development Curriculum (SDC), School/Community Intervention (SCI), Health Enhancement control curriculum (HEC)] Assessment: Pre/post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Males in SCI had significantly lower engagement in problem behaviors (violence, provoking behavior, school delinquency, substance use, sexual intercourse, condom use) than males in HEC (P-values ranged < 0.001-0.05) Males in SDC had marginally lower engagement in problem behaviors than males in HEC (P-values ranged 0.05-0.08) No significant effects were shown with females (P > .05) | Y | Y; d = 0.52 (SDC); d = 0.82 (SCI) |

| Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% youth female Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological | Intervention families demonstrated increased protective family management skills [parent-child communication, problem-solving] compared to the control group at 2-months post-txt (P = .023) | Y | N |

| Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012 | Youth 15-16 y/o and their parent (N = 502 dyads); 51% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 71.3% of pts. Lived within 150% of poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized attention-controlled trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 2 mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | Intervention youth demonstrated decreased frequency of unprotected sex (P < .01) and increased condom efficacy (P < .05) | Y | N |

| Miller et al., 2014 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 272 dyads); 57% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: Median income $1655 monthly Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: 8 years post-txt Outcome: Physical health Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention youth demonstrated significantly reduced inflammation composite scores compared to control group youth (P < .001). | Y | Y; d = −0.90 |

| Murry et al., 2005 | Youth 11 y/o and their mother (N = 332 dyads); 54% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 46.3% of pts. lived below poverty line Rural counties in GA | Design: Randomized trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt Outcome: Psychological Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families showed greater changes in targeted parenting skills than the control group at 3-mos. post-txt (P < .01). Positive changes in youth’s self-pride and sexual self-concept at post-txt was directly and indirectly impacted by improved parenting skills | Y | N |

| Murry et al., 2007 | Youth 11 y/o and their parent (N = 284 dyads); ~50% female youth Ethnicity: AA Income: ~40% received public assistance Rural counties in GA | Design: RCT Assessment: Pre-txt, 3-mos. post-txt, long-term follow-up (29 mos. post-txt) Outcomes: Psychological; Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting strategies | Intervention families demonstrated increased adaptive parenting skills at 3-mos. post-txt compared to the control group (P < .01). Increased adaptive parenting skills contributed to increased youth self-pride at 29-month follow-up (P < .01), which indirectly improved peer orientation, sexual risk intention and behavior (P < .01). | Y | Y; d = 0.49 |

| Murry et al., 2019 | Youth (6th grade) aged M = 11.4 y/o and their parents (N = 421 dyads); 54% female youth; Ethnicity: AA Income: 14% of pts. received public assistance Rural counties in TN | Design: Three-arm RCT Assessment: Pre/post-txt, long-term follow-up (~22 mos. post-txt) Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors Mechanism: Parenting | Youth findings: Tech-based youth showed a significant decrease in risky behavior engagement intention at post-txt (P = .04) and a decrease in risky behavior engagement at long-term follow-up (P = .04). Group-based youth demonstrated a significant increase in deviant peer affiliation at post-txt (P = .002) and a non-significant reduction in risky behavior at long-term follow-up (P = .58). Parent findings: Tech-based families showed significant improvements in parenting specific to sensitive topics (P = .03). Group-based families demonstrated significant increases in supportive parenting (P = .02). | Y (for tech youth) | N |

| Strong methodological rigor | |||||

| Ringwalt et al., 1996 | Youth 12-16 y/o and their parent (N = 260 dyads); 100% male youth Ethnicity: AA Income: 50% received free or reduced lunch Durham, NC | Design: Random assignment trial Assessment: Pre-txt, 18-mos. post-txt, 30-mos. post-txt Outcome: Health risk-taking behaviors | No significant pre/post change (P > .05). | – | – |

Abbreviations: AA, African American; N, No; Y, Yes.

Intervention components

The fourth aim of this review was to outline the resilience intervention components that were integrated into the 9 highly rigorous and efficacious trials in this review (see Supplementary Table S1). In line with prior research, 4 resilience intervention components were identified as core components in these trials, including racial socialization, racial identity, cultural assets, and family resilience. Across the 9 highly rigorous and efficacious trials, some trials utilized overlapping intervention programs. We identified 5 distinct intervention programs that are synthesized. All 5 (100%) of the intervention programs integrated racial socialization and family resilience components, whereas 40% (n = 2) integrated racial identity and cultural assets. Moreover, two of these programs (40%) integrated all 4 intervention components, whereas the majority (60%) included only 2 intervention components. Overall, these findings demonstrate that few rigorous, efficacious trials integrated a comprehensive array of resilience components or a comparison of such components.

Across these intervention programs, there were a variety of topics covered within these subcategories of intervention components. Regarding racial socialization intervention components, topics included cultural socialization (pride, history), preparation for bias, promotion of mistrust, egalitarianism, family heritage, literacy. Family resilience intervention components included topics of family values and roles, family routines and rules, family support, family communication, family cohesion, parental monitoring, and parental expectation-setting. Intervention components of racial identity included building positive African American self-concept and identity and learning ethnic values. Cultural assets were integrated as intervention components through discussion and activities on communalism. There was also a range of interactive approaches in which the intervention components were delivered including, videos, role-play, group discussions, games, and homework and most intervention programs were delivered by African American trained facilitators.

Given that the majority of the highly rigorous efficacious trials integrated multiple cultural and family resilience intervention components into their curriculum, it is important to consider which components served as prominent mechanisms of change. Of the 9 highly rigorous efficacious trials, 5 trials further examined their resilience intervention components as potential mechanisms driving intervention effects. Specifically, additional analyses by Miller et al.29 showed that intervention youth’s reduced inflammation scores could be partially explained by improvements in parenting skills (family resilience) from pre- to post-treatment. Similarly, Murry et al.30 found that improvements in youth’s self-pride and self-concept from pre- to post-treatment were directly and indirectly impacted by improved parenting skills (family resilience, racial socialization). Further, Murry et al.31 demonstrated that increased adaptive parenting skills (family resilience) contributed to increased youth self-pride, which indirectly improved sexual risk intention and behaviors. In line with these studies, Brody et al.28 found that intervention changes in regulated, communicative parenting (family resilience, racial socialization) had a demonstrated link to changes in youth report of parenting, which were linked to improved youth risky behavior from pre- to post-treatment. Further analyses by Brody et al.34 found that their intervention—which integrated racial socialization and family resilience—buffered the relationship between life stress and health risk-taking behaviors. Together, these findings point toward racial socialization and family resilience components as key mechanisms for positive outcomes; however, none of the trials delineated whether racial socialization or family resilience had stronger mechanistic effects on outcomes.

Discussion

Of the few existing systematic reviews that have been conducted to summarize existing family-based resilience interventions with Black adolescents and families, there are notable limitations. Specifically, prior reviews fail to examine a breadth of health-related outcomes, they do not synthesize interventions based on methodological rigor, they do not systematically examine intervention efficacy, and they do not comprehensively synthesize key resilience intervention components. Thus, the aims of the current review were to incorporate all relevant resilience trials conducted to-date and expand on these gaps of prior reviews. The current review integrated 10 resilience trials that have not been examined in prior reviews, 1 of which targeted a strengths-based physical health outcome. Further, the current review expanded on past reviews by systematically evaluating trials based on rigor, which resulted in the synthesis of 10 highly rigorous resilience trials. Based on pre-determined parameters, 9 of these trials were identified as efficacious. Moreover, this review comprehensively summarized key resilience intervention components from these trials and considered their role as prominent mechanisms of change.

While prior reviews in this area have reported on methodological rigor, they have not systematically synthesized study findings based on methodological rigor (related to study design, handling missing data, or utilizing a comparison group). The current review builds on existing literature by systematically analyzing only the 10 trials (~67% overall) with methodological rigor in the Very Strong or Strong range. Although the majority of trials in this review demonstrated strong rigor, similar strengths-based resilience trials need to be replicated in future work. The remaining 5 trials received lower rigor scores due to a small sample size, not utilizing a structured approach to handle missing data, not utilizing a comparison group, or not randomizing participants. We also found that several trials lacked standardization between their control or comparison group and the intervention, which makes it challenging to make comparisons between and within studies. For instance, some trials included an intervention group with several weeks of treatment and the control group simply received health education materials via mail. The variability in study duration and facilitator exposure between groups may have largely accounted for intervention efficacy. Additionally, ~33% of trials in the review included study designs that did not incorporate randomization and/or comparison groups. Future resilience-based interventions are needed that implement strong study designs that utilize randomized groups, consistent control/comparison groups, and structured approaches to manage missing data, while still maintaining an emphasis on participatory and community-based methods to highlight salient cultural values.

Of the 10 highly rigorous trials, the most common intervention outcomes targeted were health risk-taking behaviors and psychological outcomes. Nine of these highly rigorous trials showed intervention effects on health risk-taking behaviors, psychological outcomes, and physical health outcomes. However, only 3 trials reported their effect size. While past reviews have primarily highlighted trials targeting psychological outcomes of depressive and anxiety symptoms,9,17 the current review expanded on these reviews to include several trials that evaluated psychological outcomes of self-esteem, self-concept, and pride in Black adolescents. The current review further expands on existing work by examining resilience trials targeting physical health outcomes and health promotion behaviors among Black adolescents and families. Only 1 rigorous trial in the current review targeted physical health outcomes (eg, inflammation)29 and none of the trials in this review targeted health promotion behaviors, such as physical activity or diet. Physical health outcomes and health promotion behaviors are an important target for resilience-based interventions among Black families, considering the well-established literature base showing that racial discrimination contributes to poor physical health behaviors and health outcomes (eg, lower quality dietary intake, physical inactivity).3,4 In particular, resilience-based interventions targeting strengths-based physical health promotion behaviors and outcomes are needed, given that the majority of prior trials have utilized a deficits framework. Specifically, prior resilience trials with Black families have largely aimed to minimize health risk-taking behaviors or related risky outcomes, whereas strengths-based trials utilize an empowering intervention approach to increase positive behaviors or outcomes.10 Strengths-based trials have been largely overlooked in the literature and are needed in future work with Black families.

Although no resilience trials included in this review targeted health promotion behavior outcomes, there is a burgeoning emphasis of research in this area. A family-based resilience trial that did not meet criteria for the current review demonstrated that among Black boys aged 8-12 years old, the intervention group had significantly higher intentions to exercise compared to the control group.42 This intervention integrated racial socialization, family resilience, and cultural assets as core resilience components. Given the promising intervention effects on health-related outcomes shown in this trial42 and improved physical health outcomes in Miller et al.’s29 trial, strengths-based physical health and health promotion outcomes should be prioritized in future resilience trials with Black families. Feasibility trials are critical to build our understanding of how to continue to expand resilience interventions for Black families, such as targeting broader strengths-based outcomes, and provide opportunities to copartner with families to determine their needs.10

Findings from this review demonstrated racial socialization, racial identity, cultural assets, and family resilience were identified as core sources of resilience in highly rigorous efficacious intervention programs, in line with prior literature.9 Of the 5 intervention programs identified in this review, the majority (60%) integrated only 2 of the 4 resilience components. All (100%) intervention programs included racial socialization and family resilience as intervention components; however, few of these programs (40%) integrated racial identity or cultural assets as intervention components. Well-established data demonstrates that racial socialization and family resilience have been shown to promote psychological well-being and lower health risk-taking behaviors.9 Racial identity and cultural assets have primarily been shown to promote psychological well-being (eg, depression).6,8 Given that racial socialization and family resilience have been shown to improve a wider range of outcomes, namely health risk-taking behaviors, this may explain why these resilience factors were integrated in more trials in the current review. However, longitudinal data among African American parents and adolescents with high family communication (family resilience) has shown that racial socialization practices are significant predictors of racial identity.43 Thus, resilience interventions integrating family resilience and racial socialization may be naturally cultivating racial identity, which could be contributing to positive health-related outcomes. It is particularly important for future resilience trials to integrate racial identity intervention components, given that adolescence is a formative time of identity exploration and growth and racial identity has shown protective influences on long-term outcomes among Black youth.6,8 Overall, these findings point to a need for more integration of racial identity and cultural assets as strengths-based comprehensive resilience intervention components in future trials targeting a wider range of outcomes, including health risk-taking behaviors and physical health outcomes.

Follow-up mechanistic analyses conducted by 5 highly rigorous efficacious trials in the current review demonstrated that racial socialization and family resilience were prominent mechanisms of change for positive health-related outcomes, but analyses did not differentiate if one had a stronger mediating effect than another. Further, none of the trials analyzed racial identity or cultural assets as mechanisms, which limits our understanding of the protective role of these intervention components. To expand our understanding of the impact of resilience components on positive health-related outcomes, it will be important in future research to examine all 4 of these strengths-based components as mechanisms.

Limitations

There are notable limitations in the current review to be mindful of. The current study was limited in only including Web of Science as a database to account for gray literature. No gray literature papers met inclusion criteria for this review, however, future reviews should examine additional databases capturing grey literature. Further, the inclusion criteria for this review was limited to samples of Black adolescents aged 10-17 years old to highlight this critical developmental period for establishing positive health-related outcomes. Although findings may not be generalizable beyond Black adolescents and families, a primary focus of this review was to highlight resilience intervention components particularly salient to Black families that have been linked to positive outcomes. Additionally, we recognize that the interventions included in this review had variability in geographic location, as well as variability in the gender of adolescent samples across interventions, which could contribute to heterogeneity in cultural and familial resilience resources in the Black community. Although this review did not focus on examining these characteristics, this may be an important area for future reviews to expand on further.

This review aimed to provide an up to-date literature review and fill gaps of relevant past reviews. The current review integrated 10 studies that have not been included in prior reviews and identified 9 highly rigorous and efficacious trials. Overall, results showed initial support for the value of resilience interventions, particularly in improving health risk-taking behaviors and psychological outcomes among Black adolescents. This review supports the need for replication of highly rigorous strengths-based resilience interventions tailored for Black families. Further, this review highlights that additional work in resilience-based trials is needed to broaden outcomes of physical health, such as health promotion behaviors, including physical activity and diet. Moreover, this review demonstrates a need for a greater integration of strengths-based components of racial identity and cultural assets in resilience trials, given that the protective nature of these resilience resources against the impact of discrimination has been well-established. Additionally, future work that examines mechanistic analyses of all 4 resilience resources will provide important insights of which intervention components primarily drive intervention effects.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Annals of Behavioral Medicine online.

Author contributions

Mary Quattlebaum (Conceptualization [lead], Funding acquisition [lead], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Software [equal], Validation [equal], Visualization [equal], Writing—original draft [lead], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Dawn K. Wilson (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [supporting], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [equal], Resources [equal], Supervision [lead], Validation [equal], Visualization [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Timothy Simmons (Formal analysis [equal], Methodology [equal], Validation [equal], Visualization [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), and Pamela Martin (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Methodology [equal], Validation [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal])

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under Grant F31MD017456-02 to Mary Quattlebaum and Dawn K. Wilson; and by a NIH General Medical Science grant (T32 GM08740) to Mary Quattlebaum.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Open Science transparency statements

1) the study was registered PROPSERO; Registration ID: CRD42022339014; 2) the analytical plan for the search (terms) has been uploaded as a supplement file; 3) the data are available upon request; 4) there were no formal analyses, so the analytical code is not required; 5) the materials for extracting the study data are available upon request.