-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Julia Yamazaki-Tan, Nathan J Harrison, Henry Marshall, Coral Gartner, Catherine E Runge, Kylie Morphett, Interventions to Reduce Lung Cancer and COPD-Related Stigma: A Systematic Review, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, Volume 58, Issue 11, November 2024, Pages 729–740, https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaae048

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Many individuals with lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience high levels of stigma, which is associated with psychological distress and delayed help-seeking.

To identify interventions aimed at reducing the stigma of lung cancer or COPD and to synthesize evidence on their efficacy.

A systematic review was conducted by searching PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and CINAHL for relevant records until March 1, 2024. Studies were eligible if they described an intervention designed to reduce internalized or external stigma associated with COPD or lung cancer and excluded if they did not report empirical findings.

We identified 476 papers, 11 of which were eligible for inclusion. Interventions included educational materials, guided behavior change programs, and psychotherapeutic approaches. Interventions targeted people diagnosed with, or at high risk of developing COPD or lung cancer or clinical staff. No interventions that aimed to reduce stigma associated with lung cancer or COPD in the general community were identified. Most interventions yielded a statistically significant reduction in at least one measure of stigma or a decrease in qualitatively reported stigma.

The emerging literature on interventions to reduce stigma associated with lung cancer and COPD suggests that such interventions can reduce internalized stigma, but larger evaluations using randomized controlled trials are needed. Most studies were in the pilot stage and required further evaluation. Research is needed on campaigns and interventions to reduce stigma at the societal level to reduce exposure to external stigma amongst those with COPD and lung cancer.

Lay Summary

Many people with lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease experience stigma, such as negative judgments from others or feelings of guilt or shame. This can lead to feelings of distress and delays in seeking medical support. We reviewed existing studies that evaluated interventions aiming to reduce the stigma associated with these diseases. The results showed that there are programs and strategies that may reduce the stigma that patients with these diseases experience. The most promising programs were psychosocial interventions that included established psychological methods, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction, cognitive behavioral therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy. However, the evidence is limited because of the small number of studies and the lack of randomized trials. Most of the evidence focuses on the individual with the illness, and future research is needed on how to reduce the stigma associated with these illnesses at a community or societal level.

Introduction

Stigma refers to the devaluation applied to an individual by themselves or others due to a characteristic possessed by that person [1]. Many individuals with lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience significant stigma due to the strong association with smoking [2, 3]. A meta-analysis of studies examining the risk of developing lung cancer in those who smoked compared to those who did not found that those who smoked were nine times more likely to develop lung cancer than those who did not [4]. In an Australian epidemiological study, the hazard ratio for lung cancer among people who reported current smoking compared to those who did not was 17.7 [5]. Smoking is associated with a fivefold increase in COPD prevalence compared to never smoking [6].

Smoking is increasingly stigmatized due to its “denormalization” through public health interventions (e.g., smoking restrictions, and anti-tobacco media campaigns) that have increased negative attitudes toward smoking [7]. Mass media campaigns and smoking restrictions have been effective interventions that are associated with increased quitting and reduced uptake of smoking [8, 9]. However, there is evidence that stigma associated with lung cancer is increasing [10], and addressing stigma has been described as an “unmet public health priority” in COPD [11]. The ethics of intentionally stigmatizing people who smoke, for example, in ads invoking feelings of shame [12], has been debated, particularly because this strategy emphasizes individual rather than corporate responsibility for tobacco-related disease and because smoking is associated with social and economic inequities [7, 13].

Individuals living with tobacco-related diseases who smoke may internalize the idea that they are to blame for their disease, and judge themselves as unworthy of empathy [14]. According to the multilevel framework of Hamann et al. [15], stigma can exist on an intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community-wide, or public policy scale. Stigma can be “perceived” when experienced by other people or “internalized” when the person devalues themselves.

Lung cancer or COPD stigma often presents as reported negative judgment from others for assumed smoking behavior as a cause of the disease. For example, qualitative research has found people with these conditions experience frequent negative judgments from others due to assumed smoking status, discomfort due to media portrayals that their illness is self-inflicted, and concern that stigma will influence their clinical care and research funding for their disease [16, 17]. Some also report experiencing discomfort from a preoccupation with their smoking status by social contacts and healthcare providers [17].

Similarly, quantitative studies have found that people with lung cancer often report receiving less sympathy compared to other illnesses [10]. Caregivers of people with lung cancer also report a lack of support and stigma associated with the diagnosis of their family members or friends [14]. The stigma associated with COPD has received less attention than lung cancer, but symptoms of COPD such as coughing and shortness of breath, or the use of medical devices such as oxygen tanks represent visible markers of respiratory disease that may invite negative perceptions [3]. Community-wide stigma also leads to wider impacts, such as less research funding relative to lung cancer’s relative disease burden, and less funding for non-profit organizations focused on lung cancer [18].

Stigma impacts the well-being and treatment of those living with lung cancer and COPD. An experimental study of primary-care physician referral patterns for hypothetical patients with advanced cancer found that advanced lung cancer was less likely to elicit referral for treatment compared to advanced breast cancer [19]. Lung cancer stigmatization increases depressive symptoms, psychological distress, and memory problems, and is associated with decreased social support [2, 14, 20]. Similarly, individuals with COPD experience perceived and internalized stigma, leading to negative affect, stress, and low self-esteem [3]. The stigma associated with these two conditions has also been shown to cause marginalization, social isolation, and a perceived lack of support [3, 14]. Lung cancer and COPD-related stigma are associated with reluctance to seek timely medical care even when symptoms are present [21, 22]. Since earlier-stage diagnosis of lung cancer reduces mortality, addressing stigma as a barrier to care-seeking should be a priority.

Stigma reduction is a key step in advancing lung cancer care, and evaluations of stigma-reduction interventions are emerging. A recently published review explored interventions to reduce stigma across all cancer types and found that they showed promise, however, further research across diverse cultural contexts was recommended [23]. Due to the breadth of the review, with all types of cancer in scope, limited attention was provided to how smoking-related stigma, beliefs, and behaviors were addressed in the interventions. Our review focuses on the efficacy of stigma-reduction interventions for lung cancer and COPD, and how the interventions address smoking history and behaviors. COPD and lung cancer were combined due to their similarities, comorbidity, and shared etiology [24]. Both are strongly associated with smoking, may co-occur, have similar visible symptoms, and are usually treated by respiratory health professionals. Hence, interventions addressing lung cancer stigma may have more to learn from studies on COPD stigma than from other cancer types. We thus conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed literature describing or evaluating interventions to reduce lung cancer or COPD-related stigma. Our specific questions were: (i) what lung cancer and COPD stigma reduction interventions exist; (ii) what are their contents and features; and (iii) how effective are these interventions?

Methods

This systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and was pre-registered on PROSPERO [ID 2023 CRD42023393006].

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

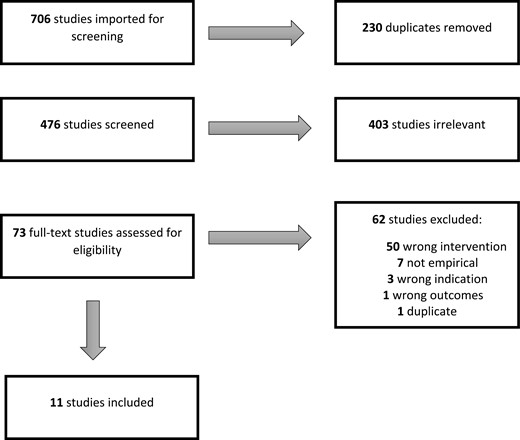

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they described an intervention designed to reduce the stigma associated with lung cancer or COPD. There were no limits based on the date the study was published, and searches were last updated on March 1, 2024. Studies identified as including people with lung cancer and/or COPD were eligible for inclusion. If the studies included people with lung cancer and/or COPD and also included people with other health conditions, they were eligible for inclusion. Anticipated populations included participants with these health conditions or who interact with them, including carers, healthcare professionals, other stakeholders, or community members. No restrictions were placed on study design or language. We excluded non-empirical studies, conference abstracts, errata, or corrigenda records, or if the full text was not available (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA diagram).

Four electronic databases were systematically searched for relevant records: PubMed (National Library of Medicine), Scopus (Elsevier), PsycINFO (Ovid), and CINAHL (EBSCO). Searches included terms for lung cancer, COPD, stigma (or shame, guilt, prejudice, or blame), and interventions (e.g., “campaign,” “program,” and “policy”). The search strategy was tailored to the database, with full details of the searches for each database provided in Supplementary File 1. All titles and abstracts were screened by two authors (JY and KM) via the Covidence web-based reference management platform (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Any conflicts were discussed until a decision on inclusion was reached. Two authors (JY and NH) completed full-text screening for each article. Conflicting decisions were resolved by consensus among KM, JY, and NH.

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

We extracted: author details, publication year, journal, article title, study type, population characteristics, country, stigma measures (if provided), intervention characteristics, and specific disease addressed. All data extraction was conducted by JY and verified by a second author (KM or NH). We narratively synthesized all studies, given their heterogenous designs. The data extraction template is provided in Supplementary File 2.

JY and NH applied the relevant JBI quality appraisal tools in duplicate for qualitative studies, case report studies, quasi-experimental studies, and randomized controlled trials [25–28]. Discrepancies in assessment were resolved through discussion between the appraisers. We report an overall risk of bias for each study as low, moderate, or high according to JBI thresholds.

Role of the Funding Source

Funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or writing of the paper, and were not involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

Summary Findings

The database searches returned 706 records (Fig. 1). Duplicates (n = 230) were removed prior to importing the references into Covidence. At title and abstract screening, 403 records were excluded because they were not relevant. At full-text screening, 62 were excluded, mostly because no stigma-reduction intervention was described. Eleven papers met the inclusion criteria, with two reporting on different aspects of the same intervention [29, 30].

Of the 10 included interventions, five were conducted in the USA, two in Australia, two in China, and one in Uganda. Eight were interventions to address lung cancer-related stigma and two addressed the stigma associated with COPD. Eight interventions were designed for symptomatic patient populations, including five interventions for lung cancer specifically [31–34], one for an at-risk group (people with smoking history at increased risk of lung cancer) [35], while one intervention evaluated in two separate studies [29, 30] was directed at oncology care providers. One intervention, delivered by trained community health workers, targeted both at-risk populations eligible for lung cancer screening, and their family members and close associates [36], while another aimed at lung cancer patients also included family members as part of the intervention [37]. Quantitative methods were used to evaluate six interventions, and qualitative methods for five. Scales used to assess stigma in quantitative studies included the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale (n = 3) [38] the Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory (n = 2) [39], and the Cancer Stigma Scale (n = 1) [40]. All of these scales contained measures of both internal stigma (e.g., feelings of shame, and guilt) and external stigma (e.g., experiences of judgment/discrimination).

We identified three types of intervention based on their primary approach: educational (three papers covering two interventions), behavioral (four interventions), and psychosocial (four interventions). Educational interventions provided information to individuals that were instructional in nature or provided reference material. Behavioral interventions involved guided behavior change (e.g., developing strategies to address perceived barriers to care, or promote earlier presentation to primary-care services, assertive communication skills), often delivered via group programs. Psychosocial interventions were designed to improve mood, coping skills, and thought patterns, usually by formal provision of a standardized therapeutic approach, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). The types of intervention were not mutually exclusive, and some interventions may have included components belonging to multiple types. We categorized them based on their primary approach for organizational purposes. One behavioral intervention consisted of pulmonary rehabilitation, which included an educational component [41].

Educational Interventions to Reduce Stigma

We identified three quantitative articles on two distinct education-based stigma-reduction interventions for lung cancer (Table 1). Both offered education in a group setting, with two articles evaluating communication skills training for oncology care providers (doctors, advanced practice providers, and nurses) at a US hospital [29, 30], and one training health professionals to provide education about lung cancer screening to those at risk of developing lung cancer. Both explicitly addressed smoking and stigma in their training for healthcare professionals. The intervention targeting oncology care providers was delivered as a single 2-hour face-to-face module that used role-play activities to practice verbal and non-verbal behaviors that convey an understanding of the patient experience and a sense of support. These included empathetic communication skills and stigma-mitigating skills for patients with lung cancer. Stigma mitigation skills included validating the difficulty of quitting smoking, normalizing nicotine addiction, and preparing patients for questions about smoking. Healthcare providers self-efficacy to communicate empathetically with lung cancer patients increased significantly following the training [29]. More than 95% of healthcare providers who completed the training reported that they had learned something new about using empathy to reduce lung cancer stigma, and about how to discuss smoking with patients with sensitivity and empathy. Patients’ experiences of stigma, measured pre- and post-intervention remained unchanged [29, 30].

Summary of Studies of Educational Interventions to Reduce Lung Cancer or COPD-related Stigma

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee et al. | 2021a | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers Lung cancer patients | 30 clinicians 175 patients | 83 46 | USA | Two-hour communication skills training for oncology care providers to alleviate stigma during patient interactions | Patient completed Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory (175 patients) Comskil Coding System (30 oncology care providers) | No change to the patient-experienced overall stigma score (p = .434). No statistically significant difference in subscales of perceived stigma, internalized stigma, and constrained disclosure | Low risk |

| Banerjee et al. | 2021b | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers | 30 | 83 | USA | Clinician self-report of usefulness and effectiveness of intervention | Self-rated clinician self-efficacy in empathetic communication and discussing smoking with patients increased (p <.001) | Low risk | |

| Williams et al. | 2021 | Pilot | People eligible for lung cancer screening | Racial/ethnic minority/medically underserved individuals eligible for lung cancer screening and their family members or close associates | 77 | 68 | USA | Lung cancer screening educational intervention including education on lung cancer stigma | Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total cancer stigma (p = .024), ratings of personal responsibility for cancer (p = .009), and perceived stigma severity (p < .0001) | Low risk |

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee et al. | 2021a | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers Lung cancer patients | 30 clinicians 175 patients | 83 46 | USA | Two-hour communication skills training for oncology care providers to alleviate stigma during patient interactions | Patient completed Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory (175 patients) Comskil Coding System (30 oncology care providers) | No change to the patient-experienced overall stigma score (p = .434). No statistically significant difference in subscales of perceived stigma, internalized stigma, and constrained disclosure | Low risk |

| Banerjee et al. | 2021b | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers | 30 | 83 | USA | Clinician self-report of usefulness and effectiveness of intervention | Self-rated clinician self-efficacy in empathetic communication and discussing smoking with patients increased (p <.001) | Low risk | |

| Williams et al. | 2021 | Pilot | People eligible for lung cancer screening | Racial/ethnic minority/medically underserved individuals eligible for lung cancer screening and their family members or close associates | 77 | 68 | USA | Lung cancer screening educational intervention including education on lung cancer stigma | Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total cancer stigma (p = .024), ratings of personal responsibility for cancer (p = .009), and perceived stigma severity (p < .0001) | Low risk |

Summary of Studies of Educational Interventions to Reduce Lung Cancer or COPD-related Stigma

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee et al. | 2021a | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers Lung cancer patients | 30 clinicians 175 patients | 83 46 | USA | Two-hour communication skills training for oncology care providers to alleviate stigma during patient interactions | Patient completed Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory (175 patients) Comskil Coding System (30 oncology care providers) | No change to the patient-experienced overall stigma score (p = .434). No statistically significant difference in subscales of perceived stigma, internalized stigma, and constrained disclosure | Low risk |

| Banerjee et al. | 2021b | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers | 30 | 83 | USA | Clinician self-report of usefulness and effectiveness of intervention | Self-rated clinician self-efficacy in empathetic communication and discussing smoking with patients increased (p <.001) | Low risk | |

| Williams et al. | 2021 | Pilot | People eligible for lung cancer screening | Racial/ethnic minority/medically underserved individuals eligible for lung cancer screening and their family members or close associates | 77 | 68 | USA | Lung cancer screening educational intervention including education on lung cancer stigma | Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total cancer stigma (p = .024), ratings of personal responsibility for cancer (p = .009), and perceived stigma severity (p < .0001) | Low risk |

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee et al. | 2021a | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers Lung cancer patients | 30 clinicians 175 patients | 83 46 | USA | Two-hour communication skills training for oncology care providers to alleviate stigma during patient interactions | Patient completed Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory (175 patients) Comskil Coding System (30 oncology care providers) | No change to the patient-experienced overall stigma score (p = .434). No statistically significant difference in subscales of perceived stigma, internalized stigma, and constrained disclosure | Low risk |

| Banerjee et al. | 2021b | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Oncology care providers | 30 | 83 | USA | Clinician self-report of usefulness and effectiveness of intervention | Self-rated clinician self-efficacy in empathetic communication and discussing smoking with patients increased (p <.001) | Low risk | |

| Williams et al. | 2021 | Pilot | People eligible for lung cancer screening | Racial/ethnic minority/medically underserved individuals eligible for lung cancer screening and their family members or close associates | 77 | 68 | USA | Lung cancer screening educational intervention including education on lung cancer stigma | Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total cancer stigma (p = .024), ratings of personal responsibility for cancer (p = .009), and perceived stigma severity (p < .0001) | Low risk |

Another intervention recruited community health workers to provide education on lung cancer screening to people from racial/ethnic minority and medically underserved populations in the USA who were candidates for screening [36]. Community health workers were trained to deliver a group-based interactive educational session focused on lung cancer screening that covered the risks and benefits of screening and the negative association between stigma and lung cancer diagnosis and screening. In the education session for those at increased risk of lung cancer, smoking cessation was discussed, and participants developed their own cancer prevention action plan. Lung cancer stigma was assessed using a scale specifically designed for non-patient populations [40]. The intervention resulted in statistically significant reductions in perceptions of cancer severity among those at-risk (e.g., “Once you’ve had cancer you’re never normal again”), and judgments of personal responsibility for developing cancer [36]. A subgroup analysis of those who used tobacco showed that perceived severity and feelings of personal responsibility (p = .007) both declined [36]. Unlike the Banerjee et al. study, this research did not examine the impact of community health worker training on their attitudes towards patients, or self-efficacy in addressing stigma and smoking in their practice.

Behavioral Interventions to Reduce Stigma

Four studies described behavioral interventions to reduce stigma, with all reporting qualitative data. Two aimed to address COPD-related stigma and two targeted lung cancer stigma. The interventions described were diverse and included a virtual reality simulation, a self-care manual, a rehabilitation program, and a depression treatment program, but all aimed to reduce disease stigma in order to increase treatment-seeking or active participation in treatment (Table 2).

Summary of Studies of Behavioral Interventions to Reduce Lung Cancer or COPD-related Stigma

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones et al. | 2018 | Evaluation | COPD or post-tuberculosis lung damage | Patients with chronic respiratory disease | 42 | Not reported | Uganda | Six-week pulmonary rehabilitation program | Self-report during interview | Increased feelings of self-value, improved relationships, reduced sense of guilt, stigma and social isolation | Low risk |

| Brown-Johnson et al. | 2019 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Health professionals | 8 | 88% | USA | Technology-based virtual-reality game. Simulation of a lung health check-up for skill-building and stigma resistance | Think-aloud narration during the intervention. Post-simulation interview | The prototype had technical issues. Users engaged emotionally with the content. Differing opinions on whether the game was clinically appropriate. Users felt the simulation would increase patient engagement with treatment and had the potential to increase patient use of stigma-resistance strategies | Moderate risk |

| Sirey et al. | 2007 | Pilot case study | COPD | Patients with COPD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | 112 | Not reported | USA | Eight-visit program including psychoeducation about depression, review of potential barriers to access to treatment, including stigma | Case study | In the case study presented, the intervention facilitated remission from depression and reduced social isolation | Low risk |

| Murray et al. | 2017 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | People at increased risk of lung cancer (currently smoking or had smoked in the past) | 20 | 40% | Australia | Primary-care nurse-led consultation to discuss and implement a self-help manual, improve self-appraisal of symptoms, and encourage help-seeking | Semi-structured qualitative interview | There was evidence that the intervention addressed stigma as a barrier to care-seeking by being delivered in a “relaxed” environment where people did not feel judged about past or present smoking behaviors | Low risk |

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones et al. | 2018 | Evaluation | COPD or post-tuberculosis lung damage | Patients with chronic respiratory disease | 42 | Not reported | Uganda | Six-week pulmonary rehabilitation program | Self-report during interview | Increased feelings of self-value, improved relationships, reduced sense of guilt, stigma and social isolation | Low risk |

| Brown-Johnson et al. | 2019 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Health professionals | 8 | 88% | USA | Technology-based virtual-reality game. Simulation of a lung health check-up for skill-building and stigma resistance | Think-aloud narration during the intervention. Post-simulation interview | The prototype had technical issues. Users engaged emotionally with the content. Differing opinions on whether the game was clinically appropriate. Users felt the simulation would increase patient engagement with treatment and had the potential to increase patient use of stigma-resistance strategies | Moderate risk |

| Sirey et al. | 2007 | Pilot case study | COPD | Patients with COPD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | 112 | Not reported | USA | Eight-visit program including psychoeducation about depression, review of potential barriers to access to treatment, including stigma | Case study | In the case study presented, the intervention facilitated remission from depression and reduced social isolation | Low risk |

| Murray et al. | 2017 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | People at increased risk of lung cancer (currently smoking or had smoked in the past) | 20 | 40% | Australia | Primary-care nurse-led consultation to discuss and implement a self-help manual, improve self-appraisal of symptoms, and encourage help-seeking | Semi-structured qualitative interview | There was evidence that the intervention addressed stigma as a barrier to care-seeking by being delivered in a “relaxed” environment where people did not feel judged about past or present smoking behaviors | Low risk |

Summary of Studies of Behavioral Interventions to Reduce Lung Cancer or COPD-related Stigma

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones et al. | 2018 | Evaluation | COPD or post-tuberculosis lung damage | Patients with chronic respiratory disease | 42 | Not reported | Uganda | Six-week pulmonary rehabilitation program | Self-report during interview | Increased feelings of self-value, improved relationships, reduced sense of guilt, stigma and social isolation | Low risk |

| Brown-Johnson et al. | 2019 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Health professionals | 8 | 88% | USA | Technology-based virtual-reality game. Simulation of a lung health check-up for skill-building and stigma resistance | Think-aloud narration during the intervention. Post-simulation interview | The prototype had technical issues. Users engaged emotionally with the content. Differing opinions on whether the game was clinically appropriate. Users felt the simulation would increase patient engagement with treatment and had the potential to increase patient use of stigma-resistance strategies | Moderate risk |

| Sirey et al. | 2007 | Pilot case study | COPD | Patients with COPD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | 112 | Not reported | USA | Eight-visit program including psychoeducation about depression, review of potential barriers to access to treatment, including stigma | Case study | In the case study presented, the intervention facilitated remission from depression and reduced social isolation | Low risk |

| Murray et al. | 2017 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | People at increased risk of lung cancer (currently smoking or had smoked in the past) | 20 | 40% | Australia | Primary-care nurse-led consultation to discuss and implement a self-help manual, improve self-appraisal of symptoms, and encourage help-seeking | Semi-structured qualitative interview | There was evidence that the intervention addressed stigma as a barrier to care-seeking by being delivered in a “relaxed” environment where people did not feel judged about past or present smoking behaviors | Low risk |

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones et al. | 2018 | Evaluation | COPD or post-tuberculosis lung damage | Patients with chronic respiratory disease | 42 | Not reported | Uganda | Six-week pulmonary rehabilitation program | Self-report during interview | Increased feelings of self-value, improved relationships, reduced sense of guilt, stigma and social isolation | Low risk |

| Brown-Johnson et al. | 2019 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | Health professionals | 8 | 88% | USA | Technology-based virtual-reality game. Simulation of a lung health check-up for skill-building and stigma resistance | Think-aloud narration during the intervention. Post-simulation interview | The prototype had technical issues. Users engaged emotionally with the content. Differing opinions on whether the game was clinically appropriate. Users felt the simulation would increase patient engagement with treatment and had the potential to increase patient use of stigma-resistance strategies | Moderate risk |

| Sirey et al. | 2007 | Pilot case study | COPD | Patients with COPD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | 112 | Not reported | USA | Eight-visit program including psychoeducation about depression, review of potential barriers to access to treatment, including stigma | Case study | In the case study presented, the intervention facilitated remission from depression and reduced social isolation | Low risk |

| Murray et al. | 2017 | Evaluation | Lung cancer | People at increased risk of lung cancer (currently smoking or had smoked in the past) | 20 | 40% | Australia | Primary-care nurse-led consultation to discuss and implement a self-help manual, improve self-appraisal of symptoms, and encourage help-seeking | Semi-structured qualitative interview | There was evidence that the intervention addressed stigma as a barrier to care-seeking by being delivered in a “relaxed” environment where people did not feel judged about past or present smoking behaviors | Low risk |

One study used qualitative interviews to evaluate a 6-week pulmonary rehabilitation intervention in Uganda. Patients reported that pulmonary rehabilitation reduced respiratory disease-associated physical and psychological symptoms and economic issues, with associated reports from participants of reduced feelings and experiences of stigma [41]. It should be noted that this study used a sample of patients with COPD or post-tuberculosis respiratory disease [41], and these results were not presented separately for each group. This may limit the generalizability of the results.

A US study evaluated a virtual reality clinic experience for people eligible for a lung health check, although this pilot study tested the intervention on health professionals [31]. The virtual clinic demonstrated what can occur during a lung health check-up and evoked the experience of stigma to allow users to practice stigma-resistance strategies [31]. The simulated experiences included “angry” or “unhelpful” clinic staff, with the simulation encouraging assertive responses to acquire the most information from the simulated staff. Health professionals participating in the pilot found it usable, and the narratives believable, and anticipated it would help consumers become more informed and assertive about their treatment. This pilot had technical issues and the authors recommended further development before testing with patients [31].

A US pilot program of an eight-session psychoeducation program about depression for people with COPD was evaluated. The program addressed barriers to COPD treatment adherence, including stigma [42]. After identifying participants’ barriers to treatment adherence, a care manager would arrange eight meetings over 6 months to administer psychoeducation about depression and COPD support and address adherence barriers. Findings for all participants were not presented, but a case study [42] described the experience of a female patient experiencing depression and feelings of hopelessness and embarrassment about having COPD. The care manager organized an increased dose of antidepressant medicine, encouraged exercise, arranged home services for help with grooming and cooking, and identified valued activities. The patient achieved full remission from depression and increased their social engagement.

A trial evaluated the Australian CHEST intervention, which aimed to increase early diagnosis of lung cancer by encouraging presentation to a doctor when symptoms appear, among people who smoked (current or past), identified from general practice clinics. A primary-care nurse discussed and implemented a self-help manual to educate participants about respiratory disease, drawing attention to the significance of symptoms, and encouraging early help-seeking [35]. Participants and primary-care nurses developed action and coping plans to encourage help-seeking and reduce barriers to treatment. Monthly reminders via SMS, email, or other communication modalities reminded participants to note their symptoms. Stigma or concerns about being “lectured” were identified as barriers to treatment seeking, with qualitative findings indicating patients felt the intervention addressed these barriers by being conducted in a non-threatening atmosphere that was non-judgmental about past or current smoking behaviors [35].

Psychosocial Interventions to Address Stigma

Four quantitative studies evaluated psychosocial interventions to reduce stigma (Table 3), all among individuals living with lung cancer. All studies provided structured, health professional-led programs using established psychosocial methods such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), mindfulness practice, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to reduce the stigma associated with lung cancer. The length of the interventions ranged from 4 weeks to 6 months.

Summary of Studies of Psychosocial Interventions to Reduce Lung Cancer or COPD-Related Stigma

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaplan et. al. | 2023 | Pilot | Lung cancer | People with lung cancer experience high levels of lung cancer stigma | 22 | 55% | USA | Six-session acceptance and commitment therapy adapted to reduce lung cancer stigma | Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory | Overall measures of lung cancer stigma decreased (p < .001), driven by the reduction in internalized stigma (p < .001). Constrained disclosure decreased from mid-to post-intervention (p = .02). Perceived stigma remained unchanged throughout the intervention (p = .25). There was deceased self-reported social isolation at the program end | Low risk |

| Tian et. al. | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 175 | 38% | China | 4-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total stigma score immediately post-intervention (p < .001), 1-month post-intervention (p = .005), and 3-months post-intervention (p < .001). Self-esteem was higher and psychological distress was lower post-intervention | Low risk |

| Chambers et al. | 2015 | Pilot | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 22 | 88% | Australia | Six weekly 50–55-minute CBT- and ACT-adapted sessions delivered over the telephone | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale, qualitative interviews | The intervention reduced overall lung cancer stigma (effect size = 0.139), and shame and social isolation subscales. Telephone delivery was acceptable to participants | Low risk |

| Ye and Wu | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 79 | Control 49% Intervention 40% | China | Nurse-led intervention program (6 months) included self-confidence cultivation, exercise, and self-care instruction, motivational communication, emotional guidance (e.g., empathic communication, mindfulness), healthcare provider communication with families | Herth Hope Index, a Chinese version of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | Scores on Herth Hope Index were higher after the intervention, and higher than the control group at 6 months (all p < .05). Scores on all dimensions of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale were lower after the intervention, and lower than the control at 6 months (p < .05) |

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaplan et. al. | 2023 | Pilot | Lung cancer | People with lung cancer experience high levels of lung cancer stigma | 22 | 55% | USA | Six-session acceptance and commitment therapy adapted to reduce lung cancer stigma | Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory | Overall measures of lung cancer stigma decreased (p < .001), driven by the reduction in internalized stigma (p < .001). Constrained disclosure decreased from mid-to post-intervention (p = .02). Perceived stigma remained unchanged throughout the intervention (p = .25). There was deceased self-reported social isolation at the program end | Low risk |

| Tian et. al. | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 175 | 38% | China | 4-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total stigma score immediately post-intervention (p < .001), 1-month post-intervention (p = .005), and 3-months post-intervention (p < .001). Self-esteem was higher and psychological distress was lower post-intervention | Low risk |

| Chambers et al. | 2015 | Pilot | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 22 | 88% | Australia | Six weekly 50–55-minute CBT- and ACT-adapted sessions delivered over the telephone | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale, qualitative interviews | The intervention reduced overall lung cancer stigma (effect size = 0.139), and shame and social isolation subscales. Telephone delivery was acceptable to participants | Low risk |

| Ye and Wu | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 79 | Control 49% Intervention 40% | China | Nurse-led intervention program (6 months) included self-confidence cultivation, exercise, and self-care instruction, motivational communication, emotional guidance (e.g., empathic communication, mindfulness), healthcare provider communication with families | Herth Hope Index, a Chinese version of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | Scores on Herth Hope Index were higher after the intervention, and higher than the control group at 6 months (all p < .05). Scores on all dimensions of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale were lower after the intervention, and lower than the control at 6 months (p < .05) |

Summary of Studies of Psychosocial Interventions to Reduce Lung Cancer or COPD-Related Stigma

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaplan et. al. | 2023 | Pilot | Lung cancer | People with lung cancer experience high levels of lung cancer stigma | 22 | 55% | USA | Six-session acceptance and commitment therapy adapted to reduce lung cancer stigma | Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory | Overall measures of lung cancer stigma decreased (p < .001), driven by the reduction in internalized stigma (p < .001). Constrained disclosure decreased from mid-to post-intervention (p = .02). Perceived stigma remained unchanged throughout the intervention (p = .25). There was deceased self-reported social isolation at the program end | Low risk |

| Tian et. al. | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 175 | 38% | China | 4-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total stigma score immediately post-intervention (p < .001), 1-month post-intervention (p = .005), and 3-months post-intervention (p < .001). Self-esteem was higher and psychological distress was lower post-intervention | Low risk |

| Chambers et al. | 2015 | Pilot | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 22 | 88% | Australia | Six weekly 50–55-minute CBT- and ACT-adapted sessions delivered over the telephone | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale, qualitative interviews | The intervention reduced overall lung cancer stigma (effect size = 0.139), and shame and social isolation subscales. Telephone delivery was acceptable to participants | Low risk |

| Ye and Wu | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 79 | Control 49% Intervention 40% | China | Nurse-led intervention program (6 months) included self-confidence cultivation, exercise, and self-care instruction, motivational communication, emotional guidance (e.g., empathic communication, mindfulness), healthcare provider communication with families | Herth Hope Index, a Chinese version of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | Scores on Herth Hope Index were higher after the intervention, and higher than the control group at 6 months (all p < .05). Scores on all dimensions of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale were lower after the intervention, and lower than the control at 6 months (p < .05) |

| Authors . | Year . | Study type . | Condition . | Target population . | Sample size . | % Female . | Country . | Description of intervention . | Outcome measure . | Key findings . | Quality appraisal: risk of bias . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaplan et. al. | 2023 | Pilot | Lung cancer | People with lung cancer experience high levels of lung cancer stigma | 22 | 55% | USA | Six-session acceptance and commitment therapy adapted to reduce lung cancer stigma | Lung Cancer Stigma Inventory | Overall measures of lung cancer stigma decreased (p < .001), driven by the reduction in internalized stigma (p < .001). Constrained disclosure decreased from mid-to post-intervention (p = .02). Perceived stigma remained unchanged throughout the intervention (p = .25). There was deceased self-reported social isolation at the program end | Low risk |

| Tian et. al. | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 175 | 38% | China | 4-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | The intervention reduced total stigma score immediately post-intervention (p < .001), 1-month post-intervention (p = .005), and 3-months post-intervention (p < .001). Self-esteem was higher and psychological distress was lower post-intervention | Low risk |

| Chambers et al. | 2015 | Pilot | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 22 | 88% | Australia | Six weekly 50–55-minute CBT- and ACT-adapted sessions delivered over the telephone | Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale, qualitative interviews | The intervention reduced overall lung cancer stigma (effect size = 0.139), and shame and social isolation subscales. Telephone delivery was acceptable to participants | Low risk |

| Ye and Wu | 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial | Lung cancer | Patients with lung cancer | 79 | Control 49% Intervention 40% | China | Nurse-led intervention program (6 months) included self-confidence cultivation, exercise, and self-care instruction, motivational communication, emotional guidance (e.g., empathic communication, mindfulness), healthcare provider communication with families | Herth Hope Index, a Chinese version of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale | Scores on Herth Hope Index were higher after the intervention, and higher than the control group at 6 months (all p < .05). Scores on all dimensions of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale were lower after the intervention, and lower than the control at 6 months (p < .05) |

One US study evaluated a six-session ACT program adapted for lung cancer stigma-reduction [34]. This intervention was offered as an in-person, telehealth, or hybrid program and demonstrated feasibility for each of these delivery modes. Overall stigma decreased over the study, mostly driven by reduced internalized stigma. Constrained disclosure also decreased from mid- to post-intervention. Scores on the perceived stigma subscale did not change over the course of the intervention [34].

A mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program recruited patients with lung cancer from the respiratory and medical oncology departments of a Chinese general hospital [33].The 4-week program consists of an in-person mindfulness program supervised by psychologists with qualifications in mindfulness training. In-person sessions were approximately 10 min long, with home exercises recommended. A statistically significant reduction in overall stigma was observed at 3 months post-intervention compared to baseline, and lower scores of perceived stigma were also reported for the intervention group at the final measurement compared to a control condition.

A six-session acceptance-focused CBT program for Australians who had received a lung cancer diagnosis included psycho-education, stress reduction skills, problem-solving, cognition-challenging, and relationship-enhancing support [32]. The intervention included six 60-min sessions delivered by telephone. The program was tailored to lung cancer patients by adding advice and care about sleeplessness and breathlessness, and a focus on acceptance as a strategy to address stigma. Specific strategies were explained to address thoughts and feelings arising from situational stigma (e.g., familial judgment, antismoking media, and advertisements), and feelings of self-blame. These included recognizing and stepping back from negative thoughts, meditation, self-kindness, self-soothing, and identifying valued activities. Participants received print resources, a book on mindfulness, and a meditation CD. Stigma was measured pre- and post-intervention using the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale and semi-structured interviews about experiences with the intervention were conducted. The total score, stigma and shame subscale, and social isolation subscale decreased at 3-month follow-up. No direct questions about stigma were asked in the qualitative interviews. Telephone delivery was perceived as acceptable, but barriers to delivering an intervention to patients who may be undertaking intensive cancer treatment were evident in the high attrition rate. Of the 56 referrals for the intervention, 16 did not commence baseline assessment, four due to incapacity, and one was deceased. Of those who completed a baseline assessment (n = 40), 15 did not begin the intervention for various reasons including reluctance to talk about cancer, already having adequate support, being overseas, or not being contactable. Of the 25 who commenced the intervention, 14 completed the 3-month survey. Reasons for non-completion were unwell/incapacity, passive refusal, unable to contact, finding the survey distressing, or participant death.

Another multicomponent intervention used a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the effectiveness of a nurse-led program for those who had lung cancer surgery in a Chinese hospital [37]. The 6-month program included self-confidence cultivation, teaching exercise skills, motivational communication, family involvement in treatment plans, and regular lectures to patients and families to increase knowledge about lung cancer and its prevention and treatment. A control group received standard nursing care. The findings showed that hope level had increased at 6 months in the intervention group, and was higher than in the control group. Self-reported stigma decreased during the intervention and was lower for the intervention compared to the control group at the end of the intervention.

Quality Assessment of Included Studies

Full quality assessment results can be found in Supplementary File 3. Of the quantitative studies, only one intervention was evaluated by a randomized controlled trial, with a waitlist control group and no blinding. One quasi-experimental study used a standard care control group. Five were evaluated with (uncontrolled) single-group designs. Future evaluations employing controlled trials are needed to clarify if observed results are due to the intervention or result from healthcare access. Using JBI’s critical appraisal tool, 10 of 11 papers were deemed to have a low risk of bias for their study design; we considered that no studies had a high risk of bias, but that one study [31] had a moderate risk of bias. This qualitative study lacked information surrounding the risk of researcher-introduced bias, for example, and did not report approval by an ethics body. Otherwise, included studies generally satisfied the majority of quality assessment criteria: studies with a lower risk of bias generally reported comparable participant groups and reliable outcome measures, although some lacked information on attrition, and some had issues with outcome data measurement [30].

Discussion

We found emerging evidence that stigma-reduction interventions can effectively reduce lung cancer or COPD-related stigma among patients with these conditions, or people at high risk of developing them, and clinical staff. Our findings on interventions focused on lung cancer align with those reported in the recent review that explored stigma reduction interventions across all cancers [23]. However, the evidence base is currently very limited. We identified only one randomized controlled trial, targeting those with lung cancer, and studies often lacked information on mediating factors such as symptom severity. Most research was conducted in high-income countries. We recommend that promising pilot interventions that have demonstrated feasibility are tested in randomized controlled trials, that disease and symptom severity are examined as a moderating factor in future studies, and that research on reducing the stigma associated with COPD and lung cancer is conducted in a greater variety of cultural contexts.

There were only two studies identified that aimed to reduce COPD-related stigma, with insufficient data to judge whether findings from interventions targeting lung cancer would be generalizable to COPD, and vice versa. There are many commonalities between the two diseases in relation to stigma (smoking as the leading risk factor, similarities in physical symptoms and molecular etiology, treatment by respiratory health professionals, and proportionately low levels of funding) [11, 15, 24], however, there are also differences that could limit generalizability. This includes the fact that those diagnosed with lung cancer have poorer prognosis and survival rates compared to those with COPD, with symptom severity and illness stage likely to be important predictors of intervention adherence and effectiveness.

Overall, educational and behavioral interventions showed promise in addressing stigma as a barrier to treatment seeking, but require further evaluation to delineate their effectiveness in reducing stigma in those experiencing, or at risk of developing lung cancer, or COPD. The most promising interventions for reducing internalized stigma in those experiencing lung cancer were psychosocial interventions that included programs conducted over an extended period of time, ranging from 6 weeks to 6 months. These were typically adapted from established psychological treatments including CBT, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and ACT. Research on the effectiveness of these programs for reducing stigma in people experiencing COPD is lacking. While it is difficult to tease apart the effects of the practical strategies taught in these programs with the empathic communication used by healthcare professionals who administer them, healthcare professionals treating people with lung cancer should consider whether elements of these therapies can be incorporated into clinical practice. Non-judgmental and stigmatizing language should be used by all healthcare professionals treating those with lung cancer or COPD, and those at risk of developing these diseases. The language guide for the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer provides some guidance on the use of stigma-reducing language (e.g., “person who smoked” rather than “smoker”) [43] and a Lung Cancer Stigma Communications Assessment Tool has been developed to assist with identifying and replacing stigmatizing language and imagery from patient and public materials [44].

Our findings align with those from other fields where stigma reduction strategies have been evaluated. For example, a review of self-stigma reduction strategies for mental illness found that psychoeducation, which aligned with our psychosocial and education categories, was the most commonly evaluated intervention type, and 8 of the 14 interventions reviewed reduced self-stigma [45]. Another review of strategies to reduce mental illness-related stigma among the public found educational strategies, and those involving contact with people who had experienced mental illness, increased knowledge, and reduced negative attitudes, however, cross-cultural interventions were lacking [46], which was also a knowledge gap identified in our review.

All studies that we identified were targeted at either the stigmatized minority (people diagnosed with or at risk of lung cancer or COPD) or clinicians. We found no studies aimed at reducing negative perceptions about patients with lung cancer or COPD among the general population. This contrasts with anti-stigma interventions for mental illness, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), obesity, and substance use, where greater attention has focused on reducing negative societal attitudes.

We found promising potential for remote and digital delivery of stigma-reduction interventions, as studies using these modalities showed positive effects. Benefits may include greater accessibility, and comfort of home setting, especially for those not close to large healthcare facilities, or with functional losses or concurrent disabilities limiting ability to travel. Some research suggests low eHealth literacy among lung cancer survivors [47], however, more recent evidence is needed to inform intervention strategies.

We did not examine intervention evaluations published only in grey literature. Such evidence would be useful to capture in future reviews. Examples of relevant interventions include two campaigns (Stop Asking the Wrong Questions and FFS! We’re losing our patients) delivered in 2019 by Lung Foundation Australia (LFA), a charity and peak body for lung health [48, 49]. Both aimed to change public attitudes to increase empathy towards people living with lung cancer, and comprised digital assets (websites, YouTube videos, social media content), and traditional media (supported by press releases). FFS (“free from stigma”) also used outdoor advertising. Stop Asking drew on the stories of 11 Australians with a loved one living (or who lived) with lung cancer, while FFS drew on the experiences of eight clinicians. Nationally representative surveys indicated the percentage of people who would first ask someone recently diagnosed with lung cancer about their smoking history fell from 40% to 29% between 2017 and 2019, while the percentage of people who agreed that those living with lung cancer were their own worst enemy fell from 21% to 8% [50]. No other public campaigns on lung disease stigma were delivered in Australia in this period. Renewed public campaigns to reduce stigma are warranted and rigorous evaluation of such campaigns would strengthen the evidence base.

Much of the stigma that is felt by those with lung cancer and COPD is due to perceptions that the individual is to blame due to a history of smoking. Some stigma-reduction campaigns have attempted to reduce stigma by educating the public that not everyone who develops lung cancer or COPD has a history of smoking. However, another strategy is to increase knowledge among the public of the commercial determinants of health, and the role of the tobacco industry in causing these diseases by selling and marketing a highly addictive product, so that stigma is reduced regardless of smoking history. Future research on the potential of such public education campaigns would be a useful next step in stigma reduction efforts.

Reducing the stigma associated with smoking-related diseases could produce substantial health benefits, including promoting engagement with screening and subsequently earlier treatment, but can also have wider benefits. Continued improvements in lung cancer survival will increase the number of people in the community with a lung cancer diagnosis. Reducing lung cancer stigma could improve their quality of life. Reducing stigma may also increase advocacy among those affected for better services, greater research funding, and also action against tobacco companies as the primary cause of illness for many. The importance of advocacy in improving outcomes and driving change has been well-documented in other fields such as breast cancer [51] and HIV [52].

Further research on what works to reduce the stigma of lung cancer and COPD is vital, as people develop these diseases after many years of smoking and also after stopping smoking. This means that the burden of these diseases will continue for some time even if smoking is virtually eliminated. Also, government goals to reduce smoking to very low levels (<5%) will continue the denormalization process and may increase smoking-related stigma. Most of the research identified in this review has focused on internalized stigma, with positive results in reducing feelings of self-blame and shame among individuals in those living with lung cancer or COPD. However, multilevel interventions are urgently required that also address broader community attitudes and societal-level stigma, to ensure that those who live with lung cancer or COPD do not experience the additional burden of stigma and discrimination [15]. This is particularly important at a time when lung cancer screening programs are being rolled out in a number of countries, with stigma identified as a potential barrier to participation in lung cancer screening programs [53, 54].

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Annals of Behavioral Medicine online.

Acknowledgements

This review was funded by a UQ Summer Vacation Scholarship awarded to Julia Yamazaki. CG and KM are supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1198301, APP2019252). NJH is supported by a PhD scholarship at Flinders University, provided through a grant from the Medical Research Future Fund (APP2008603), and a top-up scholarship funded by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1160245, APP1198301). This publication is solely the responsibility of the contributing authors and does not reflect the view of the NHMRC. Funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or writing of the paper, and were not involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Authors’ Contributions Julia Yamazaki (Data curation [lead], Formal analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [equal], Software [equal], Writing – original draft [equal], Writing – review & editing [equal]), Nathan Harrison (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [supporting], Methodology [equal], Validation [equal], Writing – review & editing [equal]), Henry Marshall (Conceptualization [supporting], Validation [supporting], Writing – review & editing [equal]), Coral Gartner (Conceptualization [equal], Funding acquisition [equal], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [supporting], Resources [equal], Supervision [supporting], Writing – review & editing [equal]), Catherine Runge (Validation [supporting], Writing – original draft [supporting], Writing – review & editing [equal]), and Kylie Morphett (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [supporting], Formal analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [lead], Resources [equal], Software [equal], Supervision [lead], Validation [equal], Writing – original draft [equal], Writing – review & editing [equal])

Ethical Approval This research was a systematic review and is exempt from ethics review. An ethics exemption from The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee was granted (2022/HE001509).

Welfare of Animals No animal research was conducted as part of this study.

Transparency Statements

Study registration: The study was pre-registered at PROSPERO (ID 2023 CRD42023393006) and is available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023393006. Analytic plan registration: N/A—no statistical analysis was completed. Availability of data: The data extraction template and assessment of study quality are available as Supplementary files. Full data extraction tables are available on request. Availability of analytic code: Not applicable. Availability of materials: The data extraction template and assessment of study quality template are attached as Supplementary files.