-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michele D Levine, Rebecca L Emery, Rachel P Kolko Conlon, Marsha D Marcus, Lisa J Germeroth, Rachel H Salk, Yu Cheng, Depressive Symptoms Assessed Near the End of Pregnancy Predict Differential Response to Postpartum Smoking Relapse Prevention Intervention, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, Volume 54, Issue 2, February 2020, Pages 119–124, https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaz026

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Depressive symptoms are prevalent during pregnancy and the postpartum period and affect risk for smoking relapse. Whether and how depression affects response to postpartum interventions designed to sustain smoking abstinence is unknown.

We examined end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms as a moderator of response to two postpartum-adapted smoking relapse prevention interventions.

Women (N = 300) who quit smoking during pregnancy were randomized to receive either a postpartum intervention focused on psychosocial factors linked to postpartum smoking (Strategies to Avoid Returning to Smoking [STARTS]) or an attention-controlled comparison intervention (SUPPORT). Women completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at the end of pregnancy. Smoking status was biochemically assessed at the end of pregnancy and at 12, 24, and 52 weeks postpartum.

End-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms moderated response to postpartum smoking relapse prevention interventions (χ2 = 10.18, p = .001). After controlling for variables previously linked to postpartum smoking relapse, women with clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms (20%) were more likely to sustain abstinence through 52 weeks postpartum if they received STARTS. In contrast, women with few end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms were more likely to sustain abstinence through 52 weeks postpartum if they received SUPPORT. Changes in the psychosocial factors addressed in the STARTS intervention did not mediate this moderation effect.

Assessment of end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms may help determine success following postpartum smoking relapse prevention interventions. Women with elevated end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms benefited from postpartum relapse prevention intervention tailored to their psychosocial needs, while those with few symptoms were more successful in postpartum intervention that used standard behavioral components.

NCT00757068.

Introduction

A majority of cigarette smokers who quit as a result of pregnancy resume smoking postpartum [1]. Evidence suggests that interventions designed specifically to address postpartum relapse may help women sustain abstinence [2–5]. We previously compared two relapse prevention interventions that had been adapted to address the postpartum period and demonstrated high rates of sustained abstinence through 1 year postpartum in both interventions [3]. Given the lack of differential efficacy in sustained abstinence between these two postpartum relapse prevention interventions, we aimed to understand which intervention worked best for whom.

There is a well-established relationship between smoking cessation outcomes and depression [6, 7]. Given that depressive symptoms are common at the end of pregnancy [8] and may be associated with postpartum smoking relapse [9], the endorsement of end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms may provide a tool to individualize postpartum relapse prevention interventions. For example, in a randomized trial of an intervention delivered during pregnancy, Cinciripini and colleagues [10] found that women with higher levels of prenatal depressive symptoms had a greater probability of postpartum sustained abstinence if they received an intensive, depression-focused intervention designed to address interpersonal and coping deficits associated with chronic depression. In contrast, those with lower prenatal depressive symptoms were more likely to remain abstinent if they received a health and wellness control intervention [10]. However, although women with fewer end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms are likelier to sustain abstinence when receiving a postpartum-adapted relapse prevention intervention [11], there is little evidence to guide the identification of intervention approaches for women with higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Accordingly, we evaluated end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms as a moderator of response to two postpartum smoking relapse prevention interventions. We hypothesized that women with more depressive symptoms would benefit more from a cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention intervention that incorporated cognitive-behavioral strategies specifically designed to address postpartum mood and stress and challenge maladaptive thoughts and beliefs about using smoking to cope with stressors and alleviate depressive symptoms. Finally, we examined changes in the select psychosocial factors that were differentially targeted in the interventions as mediators of any potential moderation effect [12].

Materials and Methods

Participants were enrolled in a larger trial investigating the efficacy of two postpartum smoking relapse prevention interventions [3]. The trial was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and participants provided written informed consent. Pregnant women who had quit smoking were randomly assigned to one of two postpartum-adapted interventions. Intervention began immediately after delivery, continued through 24 weeks postpartum, and involved brief telephone and in-person sessions. Women completed assessments of smoking status, depressive symptoms, and other psychosocial measures at the end of pregnancy and at 12, 24, and 52 weeks postpartum.

Participants and Interventions

Participants were 300 pregnant former smokers who had smoked daily for ≥1 month during the 3 months before becoming pregnant, smoked ≥5 cigarettes per day before quitting, had not smoked during the past 2 weeks, and were motivated to stay quit postpartum. Participants were recruited between 2008 and 2012. Self-report of smoking cessation was documented in the third trimester, prior to enrollment using an expired-air carbon monoxide (CO) level ≤8 parts per million (ppm) [13]. Women who reported acute psychiatric disorders warranting immediate treatment were excluded (n = 4).

Women in both interventions received behavioral smoking relapse prevention techniques, monitored urges to smoke, and received support to address cravings in high-risk situations. Both interventions were adapted to address postpartum smoking relapse and the amount and frequency of contact time was similar across interventions. Both interventions involved 13 sessions that were designed to be brief, to maximize flexibility for lower-income postpartum women, and to be conducted via telephone and in-person sessions. Strategies to Avoid Returning to Smoking (STARTS), incorporated additional cognitive-behavioral techniques to address postpartum mood, stress, and weight concerns, which have been linked to resuming smoking postpartum [14]. Thus, in STARTS, women were asked to track situations, thoughts, and feelings related to mood, stress, and weight concerns, and cognitive-behavioral strategies for addressing these psychosocial factors were discussed. The SUPPORT intervention, which served as an attention-controlled comparison, provided behavioral techniques to manage urges to smoke but did not include additional skills to address postpartum mood, stress, and weight concerns.

Assessments

Women in both intervention groups completed a prenatal baseline assessment late in the third trimester of pregnancy, prior to randomization, and intervention began immediately following delivery. Assessments of smoking status, depressive symptoms, and other psychosocial variables were completed at 12, 24, and 52 weeks postpartum.

Demographic, pregnancy-related, and smoking history information

At study enrollment, women reported age, race, income, education, and parity (coded as nulliparous [no previous births] or multiparous [at least one previous birth]). Women also completed the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [15] and reported the number of years they had smoked, number of cigarettes smoked daily prior to quitting, and when they quit smoking for their current pregnancy.

Depressive symptoms

At study enrollment and each follow-up, women completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a reliable and valid 10-item scale [16]. A cutoff score of 13 was used to distinguish women with diagnostically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms from those without [17].

Other psychosocial variables

Women completed the Perceived Stress Scale [18], a 14-item validated measure [19], which assesses the degree to which an individual appraises situations as stressful. Women also reported their self-efficacy to manage weight after quitting and smoking cessation-specific weight concerns using the valid and reliable [20] 6-item Weight Efficacy After Quitting (WEAQ) questionnaire [21].

Smoking status

At each assessment, women were interviewed about smoking using a timeline follow-back format [22]. Expired-air CO and salivary cotinine samples were also collected. Relapse was defined as the self-report of seven consecutive days of smoking, a CO >8 ppm, or a cotinine level >15 µg/L [23]. In all cases where CO or cotinine indicated smoking, women were coded as relapsed. Women who dropped out of treatment were considered to have relapsed as of the day following the last visit on which abstinence was verified. Sustained abstinence was defined as biochemically confirmed abstinence at all postpartum assessments.

Data Analytic Plan

First, we compared demographic, pregnancy-related, and smoking variables and rates of sustained abstinence between women who did and did not endorse clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms on the EPDS (see CONSORT flow diagram) [3]. We then used generalized mixed-effect models to examine the interaction between clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms and treatment condition (STARTS vs. SUPPORT) on relapse at 12, 24, and 52 weeks postpartum, as in previous research [24]. We adjusted for pretreatment factors related to postpartum relapse (age, race, education, and length of time quit prior to delivery) in each model [3]. Contrast analyses examined the simple effect of treatment condition in women with and without clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms at 12, 24, and 52 weeks postpartum.

Last, we examined the psychosocial variables (depressive symptoms, perceived stress, self-efficacy about weight management after quitting smoking, and cessation-specific weight concerns) targeted by the STARTS, but not the SUPPORT, intervention as potential mediators of the moderation effect. We tested mediated moderation on abstinence at 24 weeks postpartum when the moderation effect was strongest. Using the change between baseline and each postpartum assessment point or the absolute postpartum scores for the mediators [25], we regressed each of the mediators on treatment condition (STARTS vs. SUPPORT), the moderator (absence vs. presence of clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms), and the treatment condition by moderator interaction, controlling for the aforementioned covariates. Analyses were conducted using SAS software, Version 9.

Results

As previously reported [3], 38.0%, 33.7%, and 24.0% of the overall sample maintained abstinence at 12, 24, and 52 weeks postpartum, respectively. There were no differences between STARTS and SUPPORT in rates of sustained abstinence at any point postpartum, and depressive symptoms decreased across the postpartum period in both intervention groups [3]. Fifty-nine participants (19.7%) reported significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms. Women with and without clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms were similar in demographic, pregnancy-related, and smoking history variables, except for income (Table 1).

| . | Nondepressed (n = 241) . | . | Depressed (n = 59) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . |

| Age (years) | 25.19 | 5.77 | 24.17 | 5.07 |

| No. cigarettes smoked daily | 10.60 | 6.82 | 12.39 | 15.98 |

| No. of years smoking | 8.60 | 5.87 | 8.05 | 4.65 |

| No. previous quit attemptsa | 3.34 | 3.22 | 4.14 | 4.44 |

| FTND | 3.12 | 2.04 | 3.53 | 2.01 |

| Weeks quit at baseline | 17.76 | 11.55 | 15.45 | 12.44 |

| Prepregnancy body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.47 | 7.63 | 26.23 | 6.90 |

| Frequency | n | Frequency | n | |

| Black race | 53% | 127 | 61% | 36 |

| Education level of high school or less | 46% | 108 | 49% | 29 |

| Household annual income < $30,000b | 76% | 182 | 90% | 53 |

| Nulliparous | 54% | 130 | 44% | 26 |

| . | Nondepressed (n = 241) . | . | Depressed (n = 59) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . |

| Age (years) | 25.19 | 5.77 | 24.17 | 5.07 |

| No. cigarettes smoked daily | 10.60 | 6.82 | 12.39 | 15.98 |

| No. of years smoking | 8.60 | 5.87 | 8.05 | 4.65 |

| No. previous quit attemptsa | 3.34 | 3.22 | 4.14 | 4.44 |

| FTND | 3.12 | 2.04 | 3.53 | 2.01 |

| Weeks quit at baseline | 17.76 | 11.55 | 15.45 | 12.44 |

| Prepregnancy body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.47 | 7.63 | 26.23 | 6.90 |

| Frequency | n | Frequency | n | |

| Black race | 53% | 127 | 61% | 36 |

| Education level of high school or less | 46% | 108 | 49% | 29 |

| Household annual income < $30,000b | 76% | 182 | 90% | 53 |

| Nulliparous | 54% | 130 | 44% | 26 |

The nondepressed group includes women who scored ≤12 on the EPDS while the depressed group includes women who scored ≥13 on the EPDS, indicating clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms.

EPDS Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; FTND Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence; SD standard deviation.

aFor previous quit attempts, n = 212 in the nondepressed group and n = 48 in the depressed group.

bDifference between EPDS group on income, χ2 = 5.52, p = .02. Results of moderation analyses did not change when adjusting for this between EPDS group difference.

| . | Nondepressed (n = 241) . | . | Depressed (n = 59) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . |

| Age (years) | 25.19 | 5.77 | 24.17 | 5.07 |

| No. cigarettes smoked daily | 10.60 | 6.82 | 12.39 | 15.98 |

| No. of years smoking | 8.60 | 5.87 | 8.05 | 4.65 |

| No. previous quit attemptsa | 3.34 | 3.22 | 4.14 | 4.44 |

| FTND | 3.12 | 2.04 | 3.53 | 2.01 |

| Weeks quit at baseline | 17.76 | 11.55 | 15.45 | 12.44 |

| Prepregnancy body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.47 | 7.63 | 26.23 | 6.90 |

| Frequency | n | Frequency | n | |

| Black race | 53% | 127 | 61% | 36 |

| Education level of high school or less | 46% | 108 | 49% | 29 |

| Household annual income < $30,000b | 76% | 182 | 90% | 53 |

| Nulliparous | 54% | 130 | 44% | 26 |

| . | Nondepressed (n = 241) . | . | Depressed (n = 59) . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Mean . | SD . | Mean . | SD . |

| Age (years) | 25.19 | 5.77 | 24.17 | 5.07 |

| No. cigarettes smoked daily | 10.60 | 6.82 | 12.39 | 15.98 |

| No. of years smoking | 8.60 | 5.87 | 8.05 | 4.65 |

| No. previous quit attemptsa | 3.34 | 3.22 | 4.14 | 4.44 |

| FTND | 3.12 | 2.04 | 3.53 | 2.01 |

| Weeks quit at baseline | 17.76 | 11.55 | 15.45 | 12.44 |

| Prepregnancy body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.47 | 7.63 | 26.23 | 6.90 |

| Frequency | n | Frequency | n | |

| Black race | 53% | 127 | 61% | 36 |

| Education level of high school or less | 46% | 108 | 49% | 29 |

| Household annual income < $30,000b | 76% | 182 | 90% | 53 |

| Nulliparous | 54% | 130 | 44% | 26 |

The nondepressed group includes women who scored ≤12 on the EPDS while the depressed group includes women who scored ≥13 on the EPDS, indicating clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms.

EPDS Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; FTND Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence; SD standard deviation.

aFor previous quit attempts, n = 212 in the nondepressed group and n = 48 in the depressed group.

bDifference between EPDS group on income, χ2 = 5.52, p = .02. Results of moderation analyses did not change when adjusting for this between EPDS group difference.

End-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms and postpartum relapse

Women with clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms were significantly more likely to relapse than were women without clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms, controlling for covariates (age, race, education, number of weeks quit). Contrasts at each time point indicated the effect of depressive symptoms on relapse was significant at 12 weeks postpartum (odds ratio [OR] = 2.57, 95% confidence interval [CI]: [1.21, 5.45], χ2 = 6.05, p = .01), attenuated at 24 weeks postpartum (OR = 2.07, 95% CI: [0.92, 4.64], χ2 = 3.13, p = .08), and not significant at 52 weeks postpartum (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: [0.58, 3.26], χ2 = 0.51, p = .48).

Interaction between Intervention Condition and Depressive Symptoms on Relapse

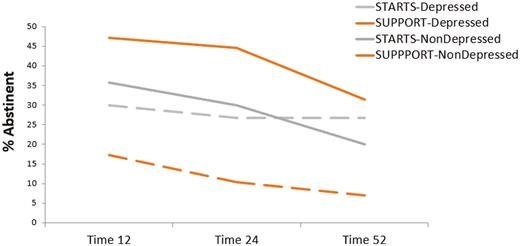

Response to postpartum intervention was moderated by end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms and remained significant after controlling for covariates (χ2 = 10.18, p = .001). As shown in Fig. 1, there were differential effects of intervention by depressive symptoms group. Contrasts indicated that among women with clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms, those who received STARTS were less likely to relapse than were those who received SUPPORT at 12 (OR = 0.19, 95% CI: [0.04, 0.83], χ2 = 5.33, p = .02), 24 (OR = 0.19, 95% CI: [0.04, 0.83], χ2 = 4.86, p = .03), and 52 weeks (OR = 0.15, 95% CI: [0.03, 0.77], χ2 = 5.17, p = .02) postpartum, controlling for covariates. Women without clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms, who received SUPPORT, were less likely to relapse than those who received STARTS at 24 weeks postpartum (OR = 1.99, 95% CI: [1.01, 3.91], χ2 = 3.89, p = .05), controlling for covariates. This effect was not significant at 12 weeks postpartum (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: [0.83, 3.06], χ2 = 1.92, p = .17) and attenuated at 52 weeks postpartum (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: [0.89, 3.47], χ2 = 2.64, p = .10).

End-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms moderate response to treatment. STARTS, Strategies to Avoid Returning to Smoking (intervention with added focus on mood, stress, and weight concerns); SUPPORT, supportive, time and attention-controlled comparison; depressed, women who endorsed clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (scores ≥13); nondepressed, women who endorsed clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (scores ≤12).

Mediated Moderation at 24 weeks Postpartum

The moderation effect at 24 weeks postpartum was not mediated by changes in depressive symptoms, perceived stress, self-efficacy for weight management after quitting smoking, or cessation-specific weight concerns (ps > .06). Neither the treatment group nor the treatment group by the end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms interaction was significantly related to any potential mediator (ps ≥ .06). Similarly, there were no significant intervention group effects or interactions between intervention group and baseline depressive symptoms in predicting any postpartum scores (ps > .15).

Discussion

Women’s end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms [26] moderated response to postpartum relapse prevention intervention. After controlling for variables associated with postpartum abstinence, the efficacy of two postpartum relapse prevention interventions differed for women with and without clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms. Women who endorsed clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms were more likely to benefit from a postpartum relapse prevention intervention with cognitive-behavioral techniques that addressed mood, stress, and weight concerns to sustain abstinence, whereas women without clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms were more likely to sustain abstinence in a supportive postpartum relapse prevention intervention.

The finding that a measure designed specifically for perinatal depressive symptoms administered at the end of pregnancy can identify women who will benefit from different approaches to sustaining abstinence postpartum suggests that capturing perinatal-specific depressive symptoms will help personalize interventions. The EPDS is feasible to administer in prenatal care settings, is the most widely used screening instrument for postpartum depression [27], and may be an inexpensive and brief aid to choosing postpartum interventions to sustain smoking abstinence.

A sizable group (20%) of women endorsed clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms and were more likely to sustain abstinence if they received a postpartum intervention that specifically targeted mood, stress, and weight concerns. Indeed, nonpregnant smokers with substantial depressive symptoms have higher abstinence rates when they receive cognitive-behavioral mood management than do smokers with fewer depressive symptoms [24]. Thus, it follows that women who were more symptomatic benefitted from postpartum intervention that incorporated additional cognitive-behavioral techniques. With this intervention, one fourth of former smokers who endorsed clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms sustained abstinence through 1 year postpartum.

The way in which interventions might differentially affect women with and without substantial depressive symptoms remains unclear. None of the putative mediators affected the interaction of treatment group and end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms on relapse. Although stress is the most frequently cited attribution for postpartum relapse by women who quit smoking during pregnancy [28], stress is also highly correlated with depressive symptoms [29], which may have limited our power to detect a mediation effect. Moreover, women’s report of stress and depressive symptoms in both interventions declined postpartum [3] suggesting that these constructs may not reflect unique mechanisms related to either intervention. It is also possible that other variables explain the interaction between depressive symptoms and treatment condition on relapse. For example, cigarette craving is an important mediator of postpartum smoking relapse among lower-income women, and stress and negative affect indirectly affect relapse through craving [30].

In addition to the lack of specific assessments designed to capture the mediation of intervention efficacy, there are other limitations to this study. Women received incentives for attending in-person visits and it is possible that these incentives affected women’s smoking. There also may be racial, economic, or other factors not assessed in this study that influence women’s perinatal depressive symptoms. Finally, it is possible that psychosocial, demographic, or pregnancy-related factors beyond those assessed in this study might have interacted with depressive symptoms. Indeed, the magnitude of the moderated effect is small, and the moderated effect of women in the SUPPORT intervention without clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms is higher than that of women with clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides evidence that a brief, commonly used measure of postpartum depressive symptoms can predict differential treatment efficacy up to 6 months postpartum in women who did and did not endorse clinically significant end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that the assessment of end-of-pregnancy depressive symptoms may be useful in tailoring relapse prevention interventions to increase rates of sustained postpartum abstinence.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Authors’ Contributions Michele D. Levine and Marsha D. Marcus were involved in conceptualzing the larger trial and Michele D. Levine, Rebecca L. Emery, Rachel P. Kolko Conlon, Marsha D. Marcus, Lisa J. Germeroth, and Rachel H. Salk conceptualized the current study. Yu Cheng conducted the analyses, All of the authors were involved in interpreting the findings and in preparing and reviewing the manuscript.

Ethical Approval The trial was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent All participants provided written informed consent in person at study enrollment.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA04174).